Connecticut Epidemiologist Newsletter • May 2023 • Volume 43, No 4

Active Tuberculosis Disease: 2022 Connecticut Case Updates and Trends

Tuberculosis (TB) is a treatable communicable disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis that spreads from person to person via airborne transmission during coughing, singing, sneezing, or speaking. It typically affects the lungs (pulmonary TB) but it may also affect other body parts. Persons with TB disease have symptoms and may be infectious if they have pulmonary TB. Persons with latent TB infection (LTBI) do not have symptoms and are not infectious but require treatment to prevent progression to TB disease (1). Until the COVID-19 pandemic, TB was the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent worldwide, ranking above HIV/AIDS (2).

Tuberculosis disease is a Category 1 reportable disease in Connecticut (CT) (3). This article highlights selected characteristics of CT 2022 TB disease cases and examines national and state trends in active TB disease from 2019 —2022.

2022 CT TB Case Characteristics

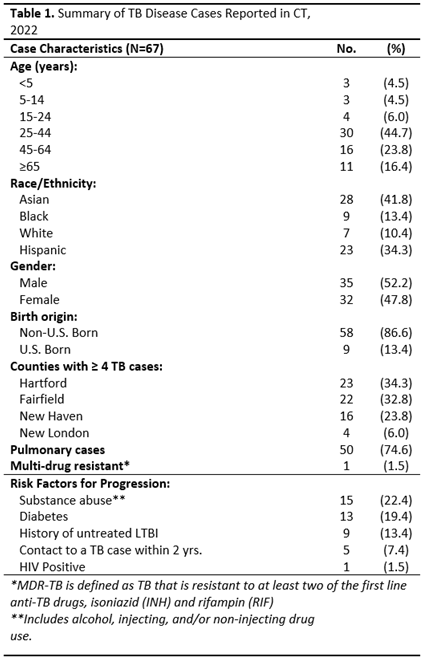

There were 67 TB disease cases reported in 2022 including 50 (74.6%) with pulmonary disease and one (1.5%) with multi-drug resistant disease. Most cases were between 15 and 64 years of age and were non-U.S. born (75% and 87% respectively) (4) (Table 1).

Nine (13.4%) cases had known LTBI prior to the diagnosis of TB disease and had been either untreated or insufficiently treated for LTBI. Other risk factors for developing TB disease included substance use (22.4%), diabetes (19.4%), and HIV (1.5%)(4,5).

Recent TB Trends — 2019 — 2022

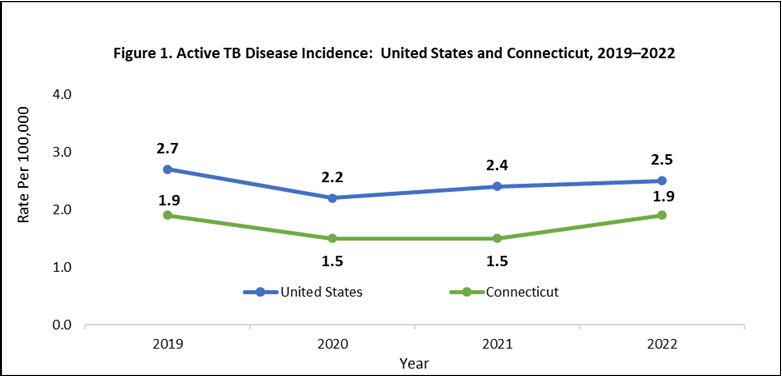

Figure 1 presents active TB disease incidence trends for the US and CT from 2019 — 2022. Nationally, there was a marked 20% decrease in TB incidence between 2019—2020 (2.7 to 2.2 per 100,000) (6). Incidence began to increase in 2021 reaching 2.5 per 100,000 by 2022 although it remained below pre-pandemic levels. (7,8).In CT, there was a similar decrease of 21.1% (1.9 to 1.5 per 100,000) in TB incidence between 2019 — 2020. Incidence returned to the pre-pandemic level in 2022 with a sharp increase of 26.6% (4).

Discussion

The incidence of active TB disease declined in CT, as in the US , between 2019 — 2020. COVID-19 transmission prevention measures likely played a role for several reasons: social distancing may have limited exposure, interruptions in healthcare access may have reduced timely access to TB testing, diagnoses, and treatment, and restrictions on immigration and international travel may have limited arrivals from countries with higher TB incidence than the US (7). As TB disease returns to pre-pandemic levels, clinicians should consider it as a potential diagnosis particularly among non-US born individuals with prolonged cough or other consistent symptoms and be aware of other risk factors such as diabetes, substance use, and HIV.

The TB disease cases with known LTBI who were either untreated or had insufficient treatment prior to the diagnosis of TB represent missed opportunities to prevent TB disease. In order to break the chain of transmission of TB infection and prevent the breakdown of LTBI into TB disease, people need to be evaluated and then fully treated for LTBI. CDC 2020 guidelines recommend two shorter regimens for LTBI treatment. The first regimen is three months of isoniazid and rifapentine (3HP) once weekly for adults and for children older than 12, including HIV-positive persons. The second regimen is four months of daily rifampin (4R) for HIV-negative adults and children of all ages (9). These shorter regimens are as effective as six to nine months of daily isoniazid and are more likely to be completed (10).

The DPH TB Control Program works with healthcare providers and local health departments to monitor new casesworks to identify and treat recently exposed contacts, and to promote screening for LTBI in a variety of settings with the goal of preventing the spread of TB. For more information, visit the DPH TB Control Program website.

Reported by F. Valipour MPH Acknowledgements A. Stratton Ph.D.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, October 20). The Difference Between Latent TB Infection and TB Disease. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/default.htm.

2. World Health Organization. (2021, October 14). Global tuberculosis report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021.

3. Connecticut Department of Public Health. Changes to the List of Reportable Diseases, Emergency Illnesses and Health Conditions, and the List of Reportable Laboratory Findings. Connecticut Epidemiologist Newsletter. Vol. 43, No.1; January 2023. Retrieved on March 31, 2023 from https://portal.ct.gov/DPH/Epidemiology-and-Emerging-Infections/The-Connecticut-Epidemiologist-Newsletter.

4. Connecticut Department of Public Health. (2022, June 15). Tuberculosis Statistics. Retrieved April 5., 2023, from https://portal.ct.gov/DPH/Tuberculosis/Tuberculosis-Statistics.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016, March 18).TB Risk Factors. Retrieved April 5, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/risk.htm

6. Deutsch-Feldman M, Pratt RH, Price SF, Tsang CA, Self JL. Tuberculosis – United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:409–414.Retrieved March 31, 2023, from http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7012a1. 7. Filardo TD, Feng P, Pratt RH, Price SF, Self JL. Tuberculosis – United States, 2021. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report 2022;71:441-446. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from https://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7112a1.

8. Schildknecht KR, Pratt RH, Feng PI, Price SF, Self JL. Tuberculosis — United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2023;72:297–303. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7212a1.

9.Sterling TR, Njie G, Zenner D, et al. Guidelines for the Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep 2020;69(No.RR-1):1-11. Retrieved March 31, 2023, from: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6901a1.

10. Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, Shang N, Gordin F, Bliven-Sizemore E, et al. Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med 2011;365 (23):2155-66

This page last updated 05/31/2023