"Stubby" at the front

"Stubby" at the front

|

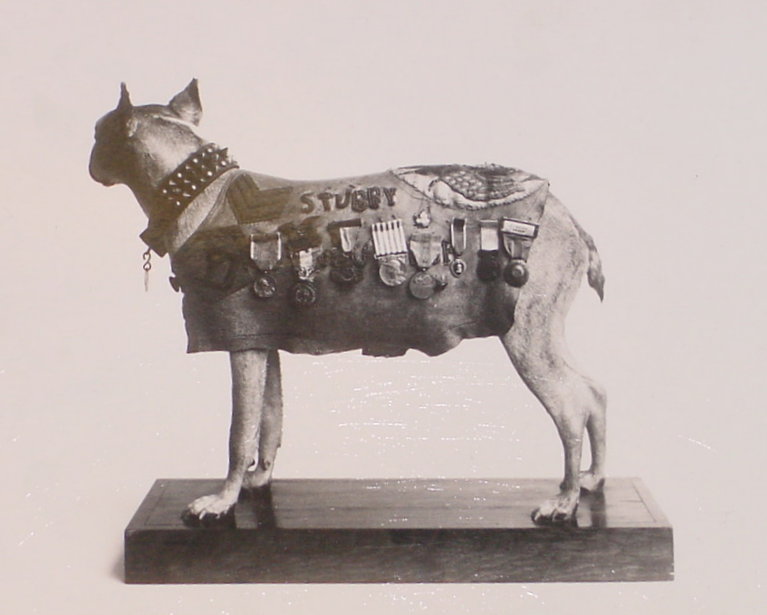

STUBBY Brave Soldier Dog of The 102nd Infantry |

|

The story of STUBBY actually starts with the beginning of the Great War in Europe. From 1914 to 1917 the French, Germans and others struggled with each other for control of France and Europe. In April of 1917 America finally entered the war and mobilized its National Guard forces. The 1st Connecticut from the Hartford area and the 2nd Connecticut from the New Haven area were sent to Camp Yale in the vicinity of the Yale Bowl for encampment and training. It was during this phase that two important things occurred. The 1st and 2nd could not muster the required number of forces between them to form a fully manned regiment of 1000 + so they were combined. The 1st and 2nd with nothing in between became the 102nd Infantry and was made a part of the 26th (YANKEE) division of Massachusetts. It was also around this time that STUBBY wandered into the encampment and befriended the soldiers. In October 1917 when the unit shipped out for France, STUBBY, by this time the "UNOFFICIAL - OFFICIAL" mascot, was smuggled aboard the troop ship S.S. Minnesota in an overcoat and sailed into doggy legend. Times were not good in France, the American Expeditionary Force was looked upon as second class soldiers, not to be trusted without French oversight and trench warfare combined with deadly gas took a toll on both the men and their spirits. STUBBY did his part by providing morale-lifting visits up and down the line and occasional early warning about gas attacks or by waking a sleeping sentry to alert him to a German attack. In April 1918 the Americans, and the 102nd Infantry, finally got their chance to prove their mettle when they participated in the raid on the German held town of Schieprey, depicted here in an original oil painting, by John D. Whiting, that hangs in the 102nd Regimental Museum in New Haven. As the Germans withdrew they threw hand grenades at the pursing allies. STUBBY got a little over enthusiastic and found himself on top of trench when a grenade went off and he was wounded in the foreleg. This occurred in the vicinity of "Deadmans Curve" on the road outside Schieprey so named because to negotiate the curve vehicles had to slow down making them an easy target for German artillery. After the recapture of Chateau Thierry the women of the town made him a chamois blanket embroidered with the flags of the allies. The blanket also held his wound stripe, three service chevrons and the numerous medals, the first of which was presented to him in Neufchateau, the home of Joan of Arc. |

|

|

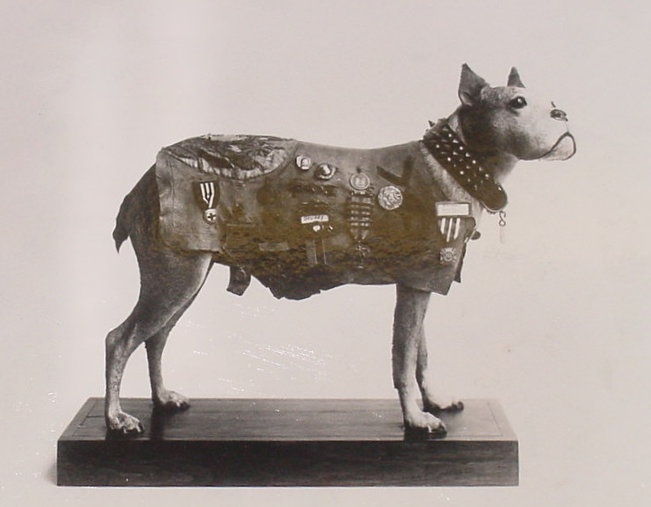

Stubby's "Uniform" with rank and medals attached on display in the Hartford State Armory |

|

|

|

| The medals and accoutrements displayed on Stubby’s Left side 3 Service Stripes Yankee Division YD Patch French Medal Battle of Verdun 1st Annual American Legion Convention Medal Minneapolis, Minnesota Nov 1919 New Haven WW1 Veterans Medal Republic of France Grande War Medal St Mihiel Campaign Medal Purple Heart Chateau Thierry Campaign Medal 6th Annual American Legion Convention | |

|

In the Argonne STUBBY ferreted out a German Spy in hiding and holding on to the seat of his pants kept the stunned German pinned until the soldiers arrived to complete the capture. STUBBY confiscated the Germans Iron Cross and wore it on the rear portion of his blanket for many years. The Iron Cross unfortunately has fallen victim to time and is no longer with STUBBY but many of his other decorations and souvenirs remain and are displayed with him today. STUBBY was also gassed a few times and eventually ended up in a hospital when his master, Corporal J. Robert Conroy, was wounded. After doing hospital duty for awhile he and Conroy returned to the 102nd and spent the remainder of the war with that unit. STUBBY was smuggled back home in much the same way as he entered the War, although by this time he was so well known that you have to suspect that one or two general officers probably looked the other way as he went aboard ship to sail home and muster out with the rest of the regiment. |

|

|

Oddly enough this not the end of the story, but rather in some ways the beginning. STUBBY became something of a celebrity. He was made a lifetime member of the American legion and marched in every legion parade and attended every legion convention from the end of the war until his death. He was written about by practically every newspaper in the country at one time or another. He met three presidents of the United States Wilson, Harding and Coolidge and was a lifetime member of the Red Cross and YMCA. The Y offered him three bones a day and place to sleep for the rest of his life and he regularly hit the campaign trail, recruiting members for the American Red Cross and selling victory bonds. In 1921 General Blackjack Pershing who was the supreme commander of American Forces during the War pinned STUBBY with a gold hero dog’s medal that was commissioned by the Humane Education Society the forerunner of our current Humane Society. |

|

| Stubby, Dog Hero of 17 Battles, Will March in Legion Parade. With the arrival of the District of Columbia delegation of the American Legion tomorrow will come the mascot of the A. E. F, Stubby, the dog hero of seventeen battles, who was decorated by General Pershing personally. Stubby served with the Twenty-Sixth Division and saw four offensives, St. Mihiel, Meuse-Argonne, Aisne- Marne and Champagne Marne. The medal that was pinned on the dog hero by General Pershing is made of gold and bears on its face the single name "Stubby", and is the gift of the Humane Education Society, sponsored by many notables including Mrs. Harding and General Pershing. The Times-Picayune Sunday, October 15, 1922 |

Stubby being decorated by General Pershing |

|

So famous was he that the Grand Hotel Majestic in New York City lifted its ban on dogs so that STUBBY could stay there enroute to one of many visits to Washington. When J. Robert Conroy went to Georgetown to study law, STUBBY became the mascot for the football team joining a long list of Georgetown Hoya’s. Between the halves he would nudge a football around the field much to the delight of the crowd. This little trick with the football became a standard feature of the repertoire of Georgetown mascots throughout the 20’s and 30’ and is thought by some to be the origin of the Half Time Show. |

|

|

Stubby the Georgetown "Hoya" |

HERO DOG HOTEL GUEST Majestic Lifts Ban for "Stubby" Decorated by Pershing. For the first time since Copeland Townsend acquired the Hotel Majestic the hard and fast rule prohibiting dogs in the hotel was waived yesterday for "Stubby" the famous mascot of New England’s veteran Twenty-Sixth (Yan- kee) Division, who arrived there en route to Washington. At the capital they will be unofficially attached to American Legion headquarters while his owner, J. Robert Conroy of New Britain, Conn., completes his vocational training courses at Georgetown University. New York Times, Sunday, December 31, 1922 |

|

In 1925 he had his portrait painted by Charles Ayer Whipple who was the artist to the capital in Washington, D.C. That portrait currently hangs in the regimental museum in New Haven. In 1926 STUBBY finally passed on. His obituary in the New York Times was three columns wide by Half a page long. Considerably more than many notables of his day.

He was eulogized by many from "Machinegun Parker" his old regimental commander to Clarence Edwards the wartime commander of the 26th Division. They all mourned his passing. His remains were preserved and presented for display purposes to the Smithsonian. |

|

| THE HARTFORD COURANT Sunday January 25, 1998 Stubby’s Legend Revived By Visit to State Armory BY ROBERT J CONRAD Courant Staff Writer |

Stubby as seen today in the Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

|

| Stubby, the hero war dog, is back in the state. A wondering mongrel, Stubby latched onto the 102nd Infantry regiment of Connecticut and accompanied it across the major battlefields of the Western Front in World War 1. He was a nothing dog who became a hero and was honored by three presidents. Now, Stubby’s mounted remains are back, dug out of storage from a museum in Washington. At the annual dog show of the First Company Governor’s Foot Guard next month, Stubby will be honored with the opening of an exhibit that will remain at the state armory for three years. "He’s kind of the unofficial grandfather of the war dog" said Col. Thomas P. Thomas, the National Guard officer working on the exhibit. Web Note: Stubby is currently on loan to the CTARNG from The SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTE National Museum of American History, Armed Forces Collections , Washington, D.C. Stubby will be returned to the Smithsonian in August, 2003. | |

|

In 1978 he was the subject of a children’s book titled STUBBY – BRAVE SOLDIER DOG. More recently he has figured prominently in a book tracing the 15,000 year history of the canine race. |

|

|

|

|

"Stubby"

SSgt William Ortiz, CT AVCRAD

|

|

|

Jack Brutus |

Although "Stubby" is widely regarded as the Grandfather of the American War Dog he was not the first by any means. Dogs were commonplace during the Civil War as companions for the soldiers and during the Spanish-American War, "Jack Brutus" became the official mascot of Company K, First Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. "Old Jack", as he was known, was considerably bigger than STUBBY and fortunately the Connecticut soldiers never got the chance to try to smuggle him anywhere since they basically spent the War encamped at various places here in the states providing coastal defense from Maine to Virginia. "Old Jack" died of spinal troubles and constipation in 1898. |

| Dogs were formally used during World War II, Korea and Vietnam in such roles as guards, and patrolling scouts but whether the dog is employed in a formal program or not you can be sure that wherever there are soldiers in need of comfort and companionship there will always be a faithful dog nearby. | |

| Photographic Evidence Supplied by: The Smithsonian Institute and the 102nd Infantry Regimental Museum | |

Settings Menu