Hunter Highlights Content

Hunter Highlights Spring 2025

Hunter Highlights Spring 2022

Forestry Field Tips for Hunting

Mountain Laurel vs. Rhododendron – Whitetail Strategies

Article by DEEP Forester Nathan Piché

The state flower of Connecticut is mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia). This woody shrub is distributed across the state and is known for growing in dense thickets that are exceptionally difficult to walk through. However, every spring they bloom beautiful bouquets of white flowers that add vibrant color to the greening landscape. Rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.) occupies a very similar niche within Connecticut’s forests, and it can often be difficult to differentiate between these two woodland shrub species. The thickets that these shrubs grow into often hold valuable secrets any hunter would wish to know.

Mountain laurel is a broad-leafed evergreen shrub. It has waxy green elliptical-shaped leaves (3 to 6 inches in length) and an ever-twisting, meandering, non-linear woody stem of 1 to 4 inches in diameter with brown, flaky bark. Its growth averages 6 to 10 feet in height but it can grow as tall as 30 feet! Flowers appear in May and June and are white or pink in color. Individual flowers measure an inch across, are hexagonal in shape, and grow in clusters 4 to 6 inches across. This shrub is native to the eastern U.S. and has other common names that include calico bush, mountain ivy, and spoonwood. Mountain laurel prefers acidic, well-drained soil and is most commonly found in hardwood forests in association with a variety of oak species, hickory, red maple and black birch.

Rhododendron refers to a broad spectrum of shrubs comprised of hundreds of species and varieties due to its popularity as an ornamental. However, one of the most common varieties that is found in the wild throughout the eastern U.S. is known as great laurel (Rhododendron maximum). Other common names for it include great rhododendron, rosebay rhododendron, and American rhododendron. This shrub shares many characteristics with mountain laurel. It is a broad-leafed evergreen shrub, has a twisting and turning woody stem of 1 to 4 inches in diameter with brown, flaky bark, grows to an average height of 6 to 10 feet but can grow as tall as 30 feet, has white and pink hexagonal shaped flowers, and prefers acidic, well drained soils. Major differences between mountain laurel and rhododendron are that the leaves of rhododendron are lanceolate in shape and average between 4 and 8 inches in length, the flowers are large, averaging between 3 and 6 inches across for each individual flower, and the shrub typically blooms in early to mid-summer in the months of June and July. Mountain laurel and rhododendron can often be found growing together on the same site. Although it is not uncommon to find rhododendron in the forests of Connecticut, mountain laurel is far more common throughout the state.

Both shrub species provide significant value to wildlife habitat, most notably in food and cover. Hummingbirds, butterflies, bees, and other pollinators are attracted to the flowers. Due to their nature to grow into dense thickets, they provide ideal cover for deer, bear, and other wildlife species that occupy eastern hardwood forests. The leaves of both species are valuable browse for deer, particularly during the winter months when many other food sources have been depleted.

From a deer hunting perspective, the key habitat feature that these shrub species provide is cover. White-tailed deer are ruminants and prey animals, which means they have evolved to browse on a variety of plant matter and then return to a secure place, safe from potential predators, within cover, to bed down and chew their cud that is regurgitated from their rumen. Mountain laurel and rhododendron provide this cover; however, the simple presence of these species does not necessarily equate to deer bedding cover, especially in areas where there are vast thickets of it. Deer will use these shrubs as cover, particularly when growing in areas that also provide them a sight and/or olfactory advantage to further protect themselves from potential predators. Also, preferred bedding locations can change based on changing food sources throughout the year.

Laurel serves as excellent cover for deer when growing on ridgetops, the points of ridges, and the leeward side of ridges. Areas such as these can be good places to search for deer sign and may be productive areas to focus hunting efforts on. Also, areas that have acorns hitting the ground directly adjacent to dense laurel cover can be very active for deer. Lastly, because both mountain laurel and rhododendron grow in such dense thickets, there may be areas that are too thick for deer to effectively travel through it. However, within these thickets, there will often be small open corridors that tunnel through the maze of woody shrubs. Many times, these corridors become game trails simply because it is the path of least resistance. These corridors have the potential to be productive hunting locations, particularly when they provide connectivity to a diversity of other habitat features, such as an area of forestland recently harvested, a vernal pool, a swamp, and/or a drainage crossing.

Mountain laurel and rhododendron fill a unique niche within our eastern hardwood forests and are incredibly valuable for wildlife. They grow so dense that it can be very challenging to walk through them. However, laurel thickets hold many secrets regarding the daily habits of whitetails and other wildlife species. Now that spring is here, many hunters are dreaming of shock gobbles and strutting toms. Now is a great time to explore laurel thickets. Unlocking their secrets now might just be the best way for you to fill your deer tag come fall.

Hunter Highlights Fall 2021

Forestry Field Tips for Hunting

Connecticut's Native Shrubs

Article by DEEP Forester Nick Zito, Photos from https://gobotany.nativetrust.org

Alder, winterberry, and witch hazel; shrubs that you may know of, but are they valuable to know for hunting?

Shrubs are a grouping of woody-stemmed, perennial species that can be evergreen or deciduous and grow to an average mature height of 15 feet. Think of these as the thick brush you have to push your way through when looking for small game.

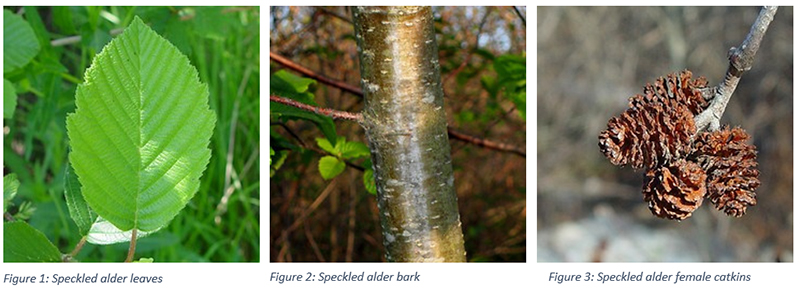

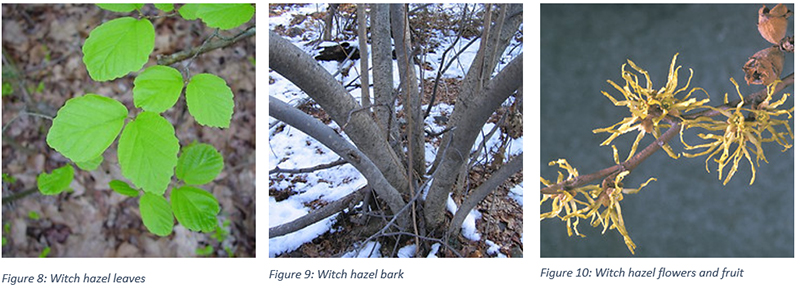

Connecticut forests host a variety of native shrubs that provide a multitude of benefits for wildlife, including food, protection from predators, and nesting and brooding sites. Three of note are speckled alder (Alnus incana subsp. rugosa), winterberry (Ilex verticillata), and witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana). These species can be found growing on lower slopes and wet sites and look similar, so it is important to identify one from the other and know which may benefit your hunting experience.

Speckled alder is often a multi-stemmed deciduous plant that can grow to be an impervious thicket, particularly in low-lying wet areas (bogs, swamps, roadside ditches, abandoned pastures, or even along lake shores or streams). The species can grow from seed germination, root suckering, or even layering (when a low branch touches the ground and forms new roots). Stems start as a reddish brown or gray with white speckles (called lenticels). As they age, the stems become smooth and gray with white lenticels. Double-toothed leaves grow alternately on the stem and are 2 to 4 inches in length. The plants have both male and female flowers on the same plant. The male flowers (i.e., catkins) hang about 1 to 3 inches from the tips of young twigs, while the female catkins are oval-shaped and only about 1/2 inch long. The female catkins closely resemble small brown pine cones.

Ruffed grouse are known to eat the buds, catkins, and seeds of speckled alder, though research suggests they are reserved as a midwinter survival food, being consumed when other food sources become scarce (Guglielmo and Karasov 1995). Speckled alder roots are also nitrogen fixing, which enriches the soil for nearby plants and creates a perfect feeding area for earthworms. This rich soil, combined with predator protection under the dense alder shrubs, provides the perfect feeding and brooding habitat for American woodcock.

Interested in finding woodcock? Your best bet is to look in alder thickets. Woodcock are amazingly camouflaged, so remember to keep your eyes and ears peeled.

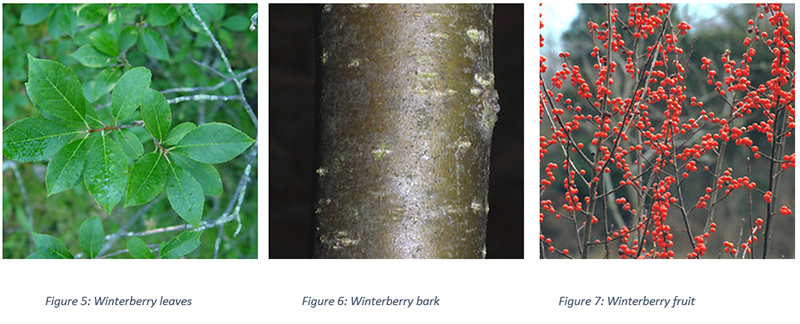

Winterberry is another shrub that also forms a dense thicket on wetter sites. You may also see winterberry in a native landscaped area. Being in the holly family, its alternate, deciduous leaves are glossy green with a broad, serrated margin. The bark is thin, smooth, and grayish brown. Winterberry is renowned for its small red fruit, which often persists long into winter after the leaves have fallen, providing a nutritious winter food source for bird species. The fruits are a favorite for eastern bluebirds and cedar waxwings, as well as game bird species. Male and female flowers are present on different plants, so berry production requires both male and female plants to be near each other.

Witch hazel is another deciduous shrub frequently found in rich or wet sites. Recognize the name? Witch hazel is commonly used in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics due to its astringent and antiseptic properties. In fact, Connecticut is home to the world’s largest producer of distilled witch hazel products.

Witch hazel leaves are alternately arranged, oval, with a broad smooth or wavy margin. The bark starts as light brown with fine hairs, growing to become smooth gray to gray-brown. Flowers and mature fruit from the previous year occur simultaneously. Blooms of yellow flowers typically occur between September and November. When the fruit is ripe, the capsule containing the seed explodes, launching the seed for distances up to 30 feet. The fruit of the plant is eaten by ruffed grouse, northern bobwhite, ring-necked pheasant, cottontail rabbit, and white-tailed deer. The clumping nature of witch hazel can provide a dense mid-story canopy layer, providing cover for ground foraging songbirds, gamebirds, small game, and white-tailed deer, particularly when oak and hickory are growing in the overstory.

When hunting in the woods or field, keep these shrubs in mind. They provide much needed cover and winter food sources for wildlife and can be a great place to find upland game birds. Do not be afraid to beat the brush in your search for the adrenaline rush that follows the heavy wing beats of a flushing ruffed grouse or pheasant, or the unmistakable twittering of the timberdoodle’s hurried flight.

Hunter Highlights Summer 2021

Forestry Field Tips for Hunting

Red Oaks vs. White OaksArticle and photos by DEEP Forester Nathan Piché

White oak (Quercus alba) is known for being the state tree of Connecticut, and for good reason. White oaks are widely distributed across the state, and are known for their strength and longevity and use in durable wood products, as well as their significant value to wildlife. Pictured right is white oak bark.

White oaks can be identified through the growing season by their leaves, which are bright green, 4 to 7 inches long, smooth around the outside of the leaf, and have rounded leaf tips. Towards the end of summer, the fruit of the tree (acorns) becomes visible as round, oblong shaped nuts with a cap that covers about one-fourth of the fruit. Once the leaves and fruits drop off the tree at the end of fall, white oak can be identified by its whitish, ash gray bark that varies from scaly on young trees to irregularly platy or blocky on older trees. Although white oak is a deciduous tree that loses its leaves in fall, many white oaks retain their leaves from the previous growing season through winter. These leaves will be dead, brown in color, and easily visible in the otherwise foliage-less forest of wintertime.

Red oak (Quercus rubra) is another common oak species found throughout Connecticut that is of significant value to wildlife. However, red oak fills a different niche for wildlife, making it important to tell the difference between red oak and white oak. The major difference one will find between the leaves of white oak and red oak is that red oak leaves have pointed tips. Red oak leaves will also turn a reddish color in fall before they drop. The fruit (acorns) of red oak are round, oblong shaped nuts that have a cap that usually only covers the base of the nut, but sometimes can cover as much as one-fourth. The bark of red oak can be identified by its long, vertical strips with rounded ridges (often looking like ski tracks in snow) running up and down the tree. Between these vertical strips will be scaly and dark reddish in color.

Both red and white oak produce acorns, which are highly sought after by many species of wildlife. Acorns are a major protein source for deer, bears, turkeys, squirrels, ducks, and countless species. However, not every tree produces a bumper crop of acorns every year. Healthy red oaks have the capacity to produce acorns every year, with large crops being produced every 2 to 5 years. White oaks can also produce acorns annually, but there may be longer intervals between large crops, 4 to 10 years, typically. Because these tree species are widely distributed across the state and growing conditions vary significantly from one site to another, many areas may not have much for acorns one year but may have a bumper crop the next and vice versa. Pictured at right is red oak bark.

Both red oak and white oak acorns drop to the forest floor at the same time of year, September and October. The main difference between the two is their palatability. Red oak acorns have more tannic acid, making them bitter, particularly when they first fall off the tree. White oak acorns have less tannic acid, making them much more palatable. This is what makes white oak acorns so valuable to wildlife when they first fall off the tree during early fall. As red oak acorns sit on the ground and get rained on, the tannic acid slowly leaches out of them, making them more palatable months after they have dropped to the ground. This is what makes red oak acorns so valuable to wildlife late in fall and through the winter months. Hunters would be wise to focus on white oak trees dropping acorns early in the season and focus on where red oak trees were dropping acorns later in the season.

Deer and turkeys will paw through the leaf litter on the forest floor, searching for acorns. All of the pawing around in the leaves is an obvious sign to the hunter looking for their quarry’s current food source. Look for areas that appear as though the leaves have been rototilled. Upon close inspection of an acorn feeding area, one will find fresh droppings, acorn caps (which are popped off when the rest of the acorn is eaten), as well as tracks. During the white-tailed deer rut, (late October through November), one might also find buck rubs and scrapes in these areas, as well. Pictured at the right is sign where deer had been feeding on red oak acorns in winter. Notice how it appears as though the snow has been rototilled as the deer dug for acorns.

If one can find an isolated oak that is dropping or had already dropped its acorns with heavy feeding sign under it, a setup downwind of this location may be productive. However, if acorn feeding sign is scattered through a large area, hunting within or on the edge of this feeding area may not result in a productive hunt because the game is scattered over a larger area and are not concentrated on any one particular feeding location. In this case, it would be wise for the hunter to focus on whatever the limiting habitat factor may be for that area. Limiting factors could be secure bedding cover for deer or good roosting trees for turkeys.

Finding sign of game feeding on acorns will not always lead a hunter directly to success. However, sign of acorn feeding often fits into a larger puzzle of habitat elements. So, get out there and start putting more of the puzzle pieces together in the areas you hunt. You might just find the missing piece needed to fill a tag.

Hunter Highlights Spring 2021

Hunter Education Requirements

Students are required to complete prerequisites before attending an in-person modified field day under the programs that were adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The firearms and bowhunting programs each have their own distinct set of prerequisites, as well as their own field days which are not interchangeable.

Firearms hunting students have their choice of taking one of two online prerequisite courses: NRA Hunter Education (free of charge) or HunterEdCourse.com ($19.99 charge). Once these are completed, the resulting certificate must be submitted by email to DEEP via DEEP.HunterEducation@ct.gov. Students must then review the videos, Connecticut Modified Firearms Hunting Certification Track: Hunting Laws and Ethics Presentation, and Treestand Safety Training. The contents of the videos are covered on the exam taken during the field day. Lastly, students must review the Control and Actions of Hunters (500’ Rule) study guide and complete the associated exam with a passing score of 100%. Once these prerequisites are complete, students can register for the Modified Firearms Hunting Field Day using their CT Conservation ID through the Connecticut Hunter Education Registration System.

Bowhunting students must complete the Online Bowhunting Training prerequisite course ($30 fee). Once this is completed, the resulting certificate must be submitted by email to DEEP via DEEP.HunterEducation@ct.gov. Students must then review the Connecticut Modified Bowhunting Certification Track: Hunting Laws and Ethics Presentation. The content of this video is covered on the exam taken during the field day. Once these prerequisites are complete, students can register for the Modified Bow Hunting Field Day using their CT Conservation ID through the Connecticut Hunter Education Registration System.

Both Modified Field Days consist of four rotations of instructor led learning and a proctored exam. The field days last approximately three hours and are not interchangeable. Students are required to wear full face coverings and follow the social distancing protocols outlined by instructors and staff at the field day event.

Turkey Hunting Tips from the National Wild Turkey Federation

For many, the start of longer days and warmer temperatures harken thoughts of blooming flowers and the twittering of songbirds as nature welcomes spring back to New England. But for the turkey hunter, our thoughts are consumed with the anticipation of the hunt; hearing thunderous gobbles and the flap of wings in the pre-dawn light; and mornings spent in the fields and woods as we witness fantastic displays and use every bit of knowledge and skill (don’t forget luck!) we possess to lure a gobbler into range of our shotgun or bow. Make no mistake, turkeys are not easy prey. Their keen eyesight makes up for their lack of smell and they can detect even the slightest amount of movement. You are encouraged to learn all you can before hitting the woods to begin your turkey hunting adventures – a safe and successful hunt depends on it. But Where to Start?

Practice Your Calling

To be successful in turkey hunting, you need to learn to talk turkey! Many hunters rely on calls to help bring the birds within shot range. Beginners usually find a box call the easiest to get a consistent sound. There are diaphragm or mouth calls, pot and striker calls made with glass or slate, box calls, wingbone calls, and many others. Some take more practice than others. Start with one call. It does not have to be the most expensive box or pot call; a good quality call will do the trick. Learn the basic sounds, like cluck, purr, putt, and yelp, to start. As your ability increases, you can add the more advanced sounds and learn to create dynamics within those sounds to keep the birds listening.

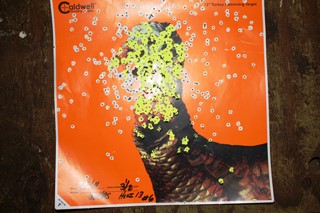

Patterning Your Shotgun

One of the most important things you can do as you prepare for the season is to pattern your shotgun. This will ensure you are ready when a gobbling tom walks your way. Spending time on the range with your gun not only helps you become familiar with its operation, but also teaches you the effective range of your choke/ammunition so you will have confidence in your ability to make an ethical and effective shot when on a hunt. Every gun-and-shell combination works differently and often only small differences are evident. Make sure to take shots at different distances (e.g., 20 yds., 30 yds., 40 yds.) to see how the pattern changes.

Finding a Place to Hunt

Ideally, you should start scouting weeks ahead of the season opening, when large winter flocks start to break up.

- Do some internet sleuthing with aerial photos and find potential public or private land you think has good hunting potential.

- Plan for some early morning trips to listen for birds gobbling on the roost, even if it just from the roadside.

- Seek landowner permission if needed.

- Go for walks to find feeding areas or confirm roosting locations. Some easily recognizable signs of turkeys include turkey droppings and areas in the woods where the leaves or pine needles look as if they have been turned over (as turkeys search for seeds and insects). You might find turkey tracks along an old logging road after a rainstorm or even a shallow turkey-sized depression of bare ground that turkeys use as a dusting area.

- Once you find birds, learn their patterns to find out where they go to feed/display in the mornings once they leave the roost, including the route they take to get there. If possible, learn where they go on sunny days and rainy days. The more you can anticipate the birds’ behavior, the better your chances of having a successful hunt.

- If possible, have a back-up hunting area in mind. You never know when the birds will throw you a curve ball or another hunter shows up at the parking area ahead of you.

*The mission of the National Wild Turkey Federation is the conservation of the wild turkey and preservation of our hunting heritage. For more information, visit nwtf.org.

Patterning a Shotgun

One of the most important pre-season preparations, and often the most overlooked, is patterning your gun for spring turkey hunting. Hunting without patterning your shotgun is akin to hunting deer without sighting in your rifle. Hunters have a responsibility to ensure their firearms are properly set to make an ethical shot.

Where to Start

First steps include choosing your ammunition and choke. Today’s ammunition and choke manufacturers offer the hunter a wide variety of choices. Begin your research online. Hunting articles and forums will give you an idea of some shell and choke combinations that work well for others with your same firearm. If your gun comes equipped with a factory tube, or you already have a tube, consult the manufacturer’s website. Manufacturers of firearms and chokes have started to post recommendations for shell and shot size for their tubes.

Shotguns, like rifles, tend to do better with certain loads. You can shoot them all, but some will perform better that others. Remember different sized loads and shells make a difference in the pattern as well. After finding some recommendations, you will need to purchase a variety of shells in the recommended shot sizes.

Patterning

The idea of patterning is to make sure your gun shoots reliably and consistently throughout your ethical kill range, and also help determine what that range is. When starting the process of patterning, have a good supply of targets. You need at least one target for each manufacturer, shot size, and distance. You can use a turkey target that is readily available for this purpose or simply take a piece of 2x3 foot poster paper and place a dot in the middle.

Start off at a distance of 10 or 15 yards; fire each one of your shells from a steady rest at a clean new target, marking each target with the pertinent information (manufacturer and shot and shell size). Move back to 20 or 25 yards, and then 30 or 35 yards and repeat the process again at each distance. Knowing that some turkey loads are lethal to 40 yards and beyond does not mean that it is always a good idea to take that shot. Just like turkey loads, hunters have an effective range as well. The most challenging part of turkey hunting and what makes it so exciting is to get the bird to come in close.

Understanding Your Pattern

Start off by laying the targets out on a large surface where you can examine each one and easily compare them. A few of your targets will obviously not make the grade and not require further examination. Remove those targets and cross that shell off your list of possibilities. Next, start checking your patterns for voids. A turkey’s head is about the size of your fist, and a void in your pattern that big could cause missed opportunities in the field. The targets that are left will require a pellet count. Draw a 10-inch circle around the bull’s-eye on your target and count every pellet in the circle; the more pellets the better. After completing your pellet count and excluding voids, you should have your load chosen for your spring hunt.

The Final Decision

When patterning your shotgun and making the final decision on your choke and shell combination, remember the reason for patterning is to make your shotgun shoot consistently. So, choose the shell and choke combination that gives you the most consistent and repeatable pattern at all ranges.

The time taken to pattern your gun will ensure you are ready when the opportunity to harvest a bird in the field presents itself.

Turkey Hunting Safety

Safety is not an accident, it is a planned outcome.

- Dress for success- wear camouflage that blends into your environment, but never wear red, white, or blue while turkey hunting.

- Sit against a large tree or rock wide enough and tall enough to shield you from hunters approaching from behind.

- Inspect your firearm and ensure it is in working order before you head out to the woods.

- Only carry the ammunition you intend to use for the gun you are carrying.

- Remember to use tick repellant.

- Carry decoys in and out of the woods covered so they cannot be mistaken for live birds.

- Carry a fluorescent orange vest to wear when moving from set to set and to cover your harvest when walking out.

- If approached by another hunter, do not wave or try to hide. Do the one thing animals cannot do, call out in a loud voice and announce your presence.

- Never stalk a turkey; it is far safer to have the bird come to you.

- Know the boundaries of the property you are hunting.

- Identify your target and verify beyond your target before shooting

Forestry Field Tips for Hunting

Identification of Pines and Hemlock

Pine, hemlock, spruce, fir, conifer, evergreen, softwoods. We often hear them referred to by many different names, but what is a conifer tree? What species are in Connecticut and how do they benefit wild game species? How can hunters identify these trees in the field to improve hunting tactics and put more wild game meat in the freezer?

A coniferous, or evergreen, tree is a grouping of species that refers to those which have needles rather than leaves and maintain needles throughout the year. Deciduous trees, also known as hardwoods, refers to the grouping of species that lose their leaves every fall and regrow them each spring.

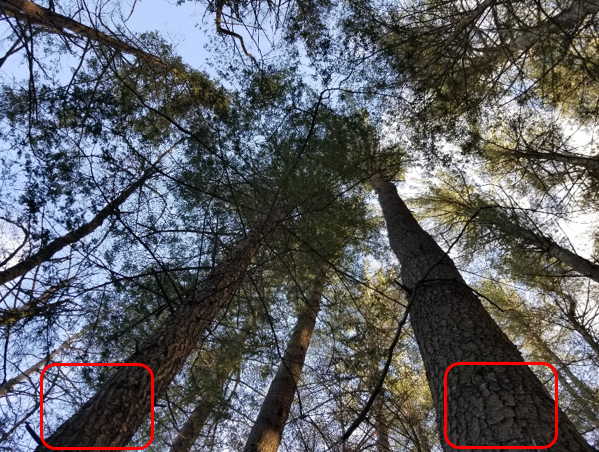

Connecticut features two primary conifer species, the Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) and the Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). White pine (pine) often grow in sandy, upland, well-drained, and/or shallow soils; often poorer quality soils that do not support vigorous hardwood species. Eastern hemlock (hemlock), similarly grow in poor-quality sites, often on shallow-to-bedrock soils and steep, north-facing slopes, as well as in poorly-drained, wet soils. Often, as in northwestern Connecticut, these species can grow well together, forming a dense, shaded forest that can harbor game species.

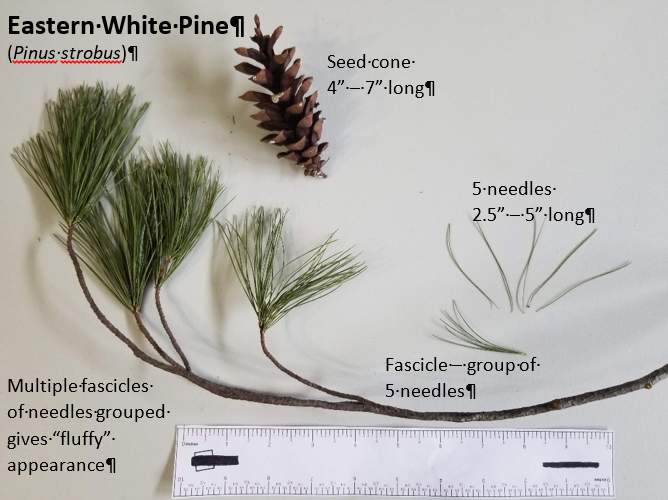

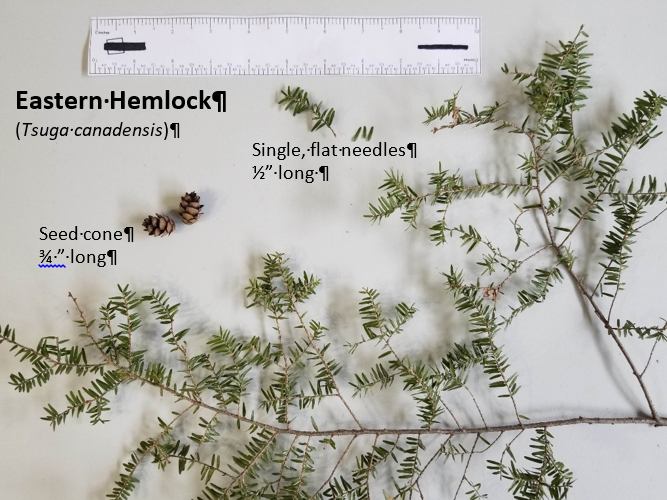

Pine and hemlock can be identified by observing key characteristics of their bark, needles, and cones:

- Pine bark can be smooth and gray-green when young, later turning reddish brown to gray-brown and developing long fissured ridges and becoming scaly and blocky with age. Pine needles are 2.5 – 5 inches long and are grouped together in “fascicles” with five needles per fascicle. Pine have larger seed cones than hemlock, measuring between 4-7 inches long.

- Hemlock have similar bark, but seemingly flatter and more widely grooved than pine, though this can vary. The bark is initially gray-brown and smooth, turning red brown and scaly with age. The needles are the biggest difference. The non-grouped, single, flat needles are ½-inch long and shiny dark green on top. Hemlock have much smaller cones than pine, measuring about ¾ inches long.

Scouting for Game

Both pine and hemlock trees benefit numerous game and nongame wildlife species by providing roosting and nesting sites for a variety of bird species, offering thermal cover, yielding limited browse and seed food sources, and serving as excellent cavity trees.

Eastern wild turkeys will often roost in pine trees at night to evade predators. The dense needles offer some protection from wind, rain, snow, and excessive cold/heat. When scouting for turkey hunting, locate areas that have some amount of pine and hemlock trees in the general vicinity. Walk underneath pine trees and locate roost trees by finding turkey droppings on the ground near the base of a tree. In older pine and hemlock stands, with an open understory, turkey will forage and display where they can see far out and have advance warning of predators. These can often be good places for a morning set-up, expecting a gobbler to fly down at first light and honor your imitation hen calls. While the birds may not always be in the pines, they seem to prefer having some pine nearby that may be used at different times of the year.

White-tailed deer are generally associated with hardwood trees and oaks but will also use dense hemlock stands for thermal cover and bedding areas. Locate groups of hemlock that provide a partial canopy covering of the forest floor. After a fresh snow fall, you will often see numerous deer sign and beds located in these areas. Go one step further and locate areas with mature red oaks mixed with a dense hemlock midstory and you can be sure to find deer sign where they bed, rest, and dig for acorns during the cold winter months.

As you venture afield, take time to pause and observe your surroundings. Be mindful of the various tree species on the landscape. Keep an eye out for areas with pine and hemlock and consider how game species may use these areas. Walking conifer areas in winter when snow has covered the ground can provide more insight on how wildlife use an area and additional knowledge about wildlife habits.

Photo 1: View of hemlock (left) and white pine (right) bark. Notice the hemlock has longer fissures, while the pine appears scaly/blocky.

Photo 2: View of same hemlock (left) and white pine (right) crowns. Notice how the hemlock is overtopped by the pine and the pine seems “fluffier”.

Photo 3: View of white pine branch, fascicle, needles, and seed cone.

Photo 4: View of hemlock branch, needles, and seed cone.

Photo 5: Heavily used deer trail after fresh snow under hemlock trees. This trail is on the edge of an area with mostly hardwood trees to the right. Deer travel this transition edge habitat between the hemlock and hardwood areas and escape down into the hemlock and lowland areas for cover when threatened.

Photo 6: Same hemlock area with two deer beds seen in photo with several more outside the photo. Deer will bed in areas of hemlock for thermal protection, cover, and to get out of snow, rain, and wind. They can watch for predators in the open understory.