American Shad (Alosa sapidissima) - Native

A 20-inch adult American shad from the Shetucket River.

Identification. Cheek patch deeper than wide. Tongue is visible in profile when mouth is held open. A dark spot on shoulder sometimes followed by several others. Lower jaw does not rise steeply within mouth. Mouth slightly larger than other herring (end of jaw to middle of eye in juveniles and to back of eye in adults). Gray to bluish green on back when alive, silver on sides, white on belly. Snout of juveniles slightly more pointed than other herring.

Size. Commonly 15 to 24 inches. Conn. State Record 9.3 pounds, 25.8 inches. Max. reported size 30 inches. World Record 11.3 pounds.

A 3-inch juvenile Connecticut River American shad.

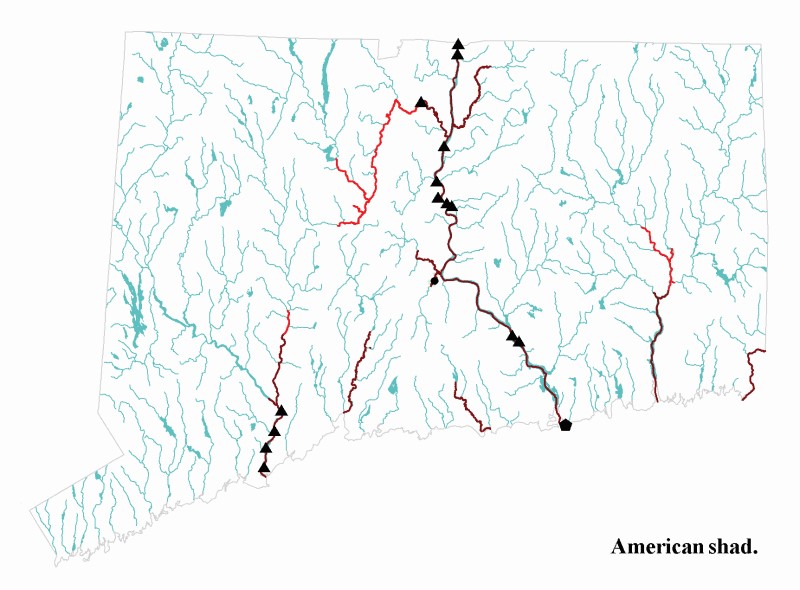

Distribution. Atlantic Coast from New Brunswick to central Florida. Introduced to the West Coast. In Connecticut, spring runs of shad occur in all major rivers (Connecticut, Housatonic, Pawcatuck and Thames), with the largest run occurring in the Connecticut River. Minor runs also occur in the Quinnipiac, Hammonasset and East rivers.

All maps created in 2009. See CT DEEP Fish Community Data for updated distributions.

Habits. American shad spend their adult lives at sea and usually return to the river of their birth to spawn. Shad will swim farther upstream than any other herring. In the Connecticut River, shad have migrated as far north as Bellows Falls, Vermont (272 miles from Long Island Sound), navigating three dams along the way via fishways. Some adult shad migrate back out to sea after spawning, but spawning stress is great and dead shad are a common sight during late spring. Juveniles spend the summer and fall in the rivers and migrate to the ocean in the late fall. Although shad cease feeding during their spawning runs (they feed on zooplankton when at sea), they will strike small jigs and spinners during this time.

Comments. The American shad is the largest of Connecticut’s herring species. In 2003, the American shad was designated Connecticut’s “State Fish.” Until the mid-1700s, eating shad was considered “disreputable,” but the fish gained favor during the Revolutionary War as salmon numbers dwindled. Commercial fisheries developed in a few of the state’s rivers, but only the Connecticut River fishery survived after others collapsed due to the construction of dams. Although the Connecticut River run is at a fraction of its historical levels, it has recovered considerably during the past 50 years and is currently one of the largest runs on the East Coast. On calm, late summer evenings on the Connecticut River, thousands of small, silvery juvenile shad can be observed “popping” out of the water in pursuit of minute insects.

Close-up of heads of juvenile American shad (top) and blueback herring (bottom). The most reliable way of distinguishing an American shad from other herrings is the relative shape of the cheek patch.

Text and images adapted from Jacobs, R. P., O'Donnell, E. B., and Connecticut DEEP. (2009). A Pictorial Guide to Freshwater Fishes of Connecticut. Hartford, CT. Available for purchase at the DEEP Store.