The Freshwater Mussels of Connecticut

The text, illustrations and photographs used on these pages were prepared for the DEEP Wildlife Division by Ethan Nedeau. All images and photographs are copyright protected.

The text, illustrations and photographs used on these pages were prepared for the DEEP Wildlife Division by Ethan Nedeau. All images and photographs are copyright protected.

Have you ever found large clams along a riverbank or lake shore? Have you wondered where these came from, or what role they play in natural ecosystems? The "clams" you found are likely freshwater mussels—they inhabit most of Connecticut's large streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes. Mussels spend most of their lives partially buried, sucking water into their bodies, filtering it to remove food, and pumping the rest back into the environment. These “living filters” play an important role in natural ecosystems by helping to clean our water bodies, eating algae and zooplankton, and providing food for many types of fish and mammals. Mussels often comprise the largest proportion of animal biomass in a waterbody and they store enormous amounts of minerals and nutrients. Did you know that some of them are very rare, and protected by Connecticut's endangered species laws?

Download (35pp.) The Freshwater Mussels of Connecticut

Freshwater Mussel Fact Sheets

Eastern Pearlshell

Dwarf Wedgemussel

Triangle Floater

Brook Floater

Creeper

Eastern Elliptio

Eastern Floater

Alewife Floater

Eastern Pondmussel

Tidewater Mucket

Yellow Lampmussel

Eastern Lampmussel

The Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection has produced the state's first field guide to its freshwater mussels. This user-friendly guide provides the following:

- General information about the biology, ecology, and conservation of freshwater mussels;

- Illustrations and diagrams that teach you how to identify the State's freshwater mussels;

- Species accounts that include color photographs, illustrations, and information about identification, habitat, range, and conservation;

- Information on two exotic bivalves that are found in Connecticut—the zebra mussel and Asiatic clam;

- Methods of finding and reporting freshwater mussels, along with a standard survey form.

Educators are encouraged to use the field guide in curriculum planning and field trips. Copies can be ordered from Laura Saucier, Sessions Woods Wildlife Management Area, PO Box 1550, Burlington, CT 06013; email: laura.saucier@ct.gov; phone: 860-424-3101.

Life Cycle of Freshwater Mussels

Freshwater mussels have a remarkable life cycle. Male mussels release sperm into the water, and sperm are then filtered by female mussels. The fertilized eggs develop into microscopic larvae called glochidia. Glochidia look like tiny mussels, and they are parasites that must attach themselves to the fins or gills of a fish. Mussels are specific about the fish they parasitize—for example, the alewife floater is only known to parasitize the alewife, Alosa pseudoharengus. After being attached to a fish for one to several weeks, glochidia let go of the fish and sink to the bottom of the waterbody, where they will spend the rest of their lives. Most mussels live eight to 20 years, but the eastern pearlshell, found in small trout streams throughout Connecticut, has been reported to live over 100 years!

Identifying Freshwater Mussels

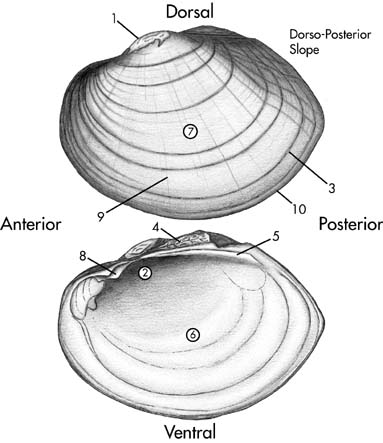

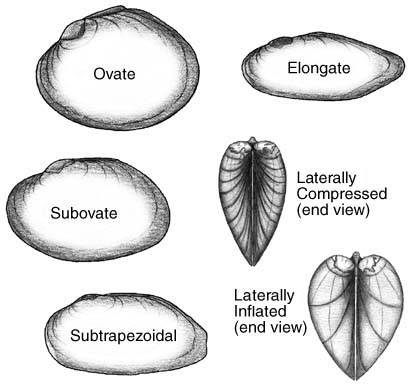

It may seem a little tricky at first, but with practice anyone can become good at identifying freshwater mussels. Identification relies on size, shape, color, and other morphological traits. Below are some illustrations and technical words that are used when identifying freshwater mussels.

1. BEAK: prominent raised area along dorsal edge, usually eroded

2. BEAK CAVITY: recessed area on the inside of the valve, under the beak

3. GROWTH LINE: dark concentric lines on the shell that show periods of growth

4. HINGE: area of connection between the two valves, and includes connective tissue and hinge teeth

5. LATERAL TEETH: thin elongate teeth located along the hinge

6. NACRE: the smooth mother-of-pearl shell material on the inside of the valve

7. PERIOSTRACUM: outer lining of the valve

8. PSEUDOCARDINAL TEETH: short stout teeth located below or just anterior to the beak

9. SHELL RAYS: faint lines that radiate from the beak, perpendicular to growth lines

10. VALVE: one of the opposing halves of a mussel shell.

Terms used to describe the shape of cells:

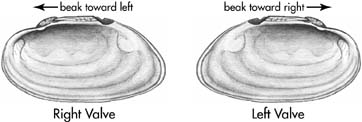

Right vs. Left Valve - Place the valve in your hand with the nacre facing toward you and the beak pointing up. If the beak is toward the right, it is the left valve, and if the beak is toward the left, it is the right valve.

Surveying and Reporting Freshwater Mussels

The Connecticut DEEP wants to learn more about its freshwater mussel resources. Conducting an intensive statewide survey is a difficult task, and therefore the State is encouraging citizens to report mussel data to the DEEP. Species records and location information will then be entered into a comprehensive database, which will be used in conservation and planning activities.

Freshwater mussels are surprisingly easy to find, making them ideal animals for environmental education lessons and volunteer monitoring programs. Students and volunteers can use survey methods similar to those of scientists, and have a good chance of finding rare species.

The field guide provides guidelines for surveying, identifying, and reporting freshwater mussels to the DEEP. This web page provides some additional information to help Connecticut's citizens become mussel watchers.

Surveying Mussels

Three common survey methods are searching the shoreline for dead shells, wading in shallow water with a clear-bottom bucket, and snorkeling.

Shoreline Searches: Walk along the riverbank or lake shore and look for shells. This method is a safe and easy way to find out what lives in a water body and allows you to collect shells without killing any animals.

Bucket Surveys: Using a plastic pail fitted with a clear bottom, you can wade in shallow water and peer through the bucket. This survey method works well in shallow water (< 3 feet) and allows you to see animals situated in the substrate. Clear-bottom buckets are perhaps the safest and best way for students and volunteer groups to survey mussels in shallow water. Buckets are fun to make, and are a great way to become familiar with the aquatic life of stream and lake bottoms. Making a clear-bottom bucket.

Snorkeling: For those people with snorkel gear, snorkeling can be a fun way to search for mussels. Snorkeling allows you to survey large areas, in deeper water, and see live undisturbed mussels up-close.

When searching for mussels, always beware of potential dangers such as poison ivy on the stream banks, slippery banks and rocks, deep mud, broken glass, pollution, dangerous flow conditions, heavy boat traffic and other hazards. Safety is the top priority! Please respect the rights of private property owners when accessing potential survey areas.

Reporting Mussels

When submitting mussel distribution information to the DEEP, you need to include specific information about the survey site and what you found. We have provided a Field Survey Data Form that you can download, fill out on the computer, print, and mail to the DEEP. With the form, please include any photographs, maps, or drawings of what you found and where you found it.

Submit completed data forms to Laura Saucier, Sessions Woods Wildlife Management Area, PO Box 1550, Burlington, CT 06013; email: laura.saucier@ct.gov; phone: 860-424-3101.

Content last updated on September 13, 2018.