One century ago, with industrialization in full swing, railroads crisscrossing the landscape, the flight to cities from the farmlands well under way, and every neighboring state having lands set aside for their own state parks, Connecticut finally made its move.

It had taken four years just to get to the starting line. In 1909, legislation was introduced to protect the lower Connecticut River, but it did not pass.

Two years later the General Assembly appointed a temporary State Park Commission to report on the need, desirability of a state park system and to consider localities best suited for state parks. By early 1913 the report was in; the time was right in Connecticut to meet the growing demands of an increasingly congested population, and to secure for public enjoyment what was rapidly becoming unaffordable real estate.

The report was amenable to all, and when the Governor gave his approval in mid-year, the tables were set for the new State Park Commission to hold its first meeting by the end of September.

Meeting Number One

So it was at 11 AM on Monday, September 29, 1913 in Room 13 of the New Haven County courthouse the six-appointed commissioners held the initial meeting of the Connecticut State Park Commission. The first order of business was the election of post-Civil War General Edward Bradley, of New Haven, as chairman. Bradley had been Chair of the 1911 temporary commission and was the unanimous choice to lead. Other commissioners hailed from New Haven, Hartford and Middletown and were influential and well known in their respective communities.

So it was at 11 AM on Monday, September 29, 1913 in Room 13 of the New Haven County courthouse the six-appointed commissioners held the initial meeting of the Connecticut State Park Commission. The first order of business was the election of post-Civil War General Edward Bradley, of New Haven, as chairman. Bradley had been Chair of the 1911 temporary commission and was the unanimous choice to lead. Other commissioners hailed from New Haven, Hartford and Middletown and were influential and well known in their respective communities.

|

The six member State Park Commission held its first meeting on September 29, 1913. General Edward Bradley, second from right, was unanimously chosen as Chair, a position he held until he passed away in January, 1917. |

It was immediately important for them to physically begin a state park system. But any thought of acquisition was premature until, as recommended in the 1911 report, there could be an investigation of the potential park sites around the state. To do this would take a special individual and on March 1, 1914 the State Park Commission hired its first employee - Albert M. Turner. Turner was a Connecticut Yankee born in 1868 and raised in the Northfield section of Litchfield. He brought to the position his background as a Yale educated engineer and several years of personal experience in various planning capacities. He hit the ground running and within seven months he had traversed the entire coastline from the Rhode Island border to New York State, visited fifty lakes forty-acres or more in size, and visited dozens of the highest peaks and the lower portions of the major rivers in the state. He recommended, in each category, those locales best suited to becoming a state park. And his vision was not just a collection of the best, highest and prettiest places. Turner had mentally compiled those locations which, when taken together, would form an entire system of state parks. His work in the spring and summer of 1913 was the very basis for the park system Connecticut holds in such high esteem one-hundred years later.

| Connecticut native Albert M. Turner, the first state park employee, began his work on March 1, 1914 at age 46 and held the position for 28 years. He personally assessed the resources of the entire state before compiling a collection of locations that form the basis of today’s state park system. |  |

Getting going

Once Turner’s inventory was complete, it was up to the commissioners to get the work done. There was however one nagging problem, money. The Commission had been given a budget of $20,000 for their first two years, but with an acre of shoreline that featured beach front and a buildable upland area selling for $6,500, the money allotted would not go far.

Once Turner’s inventory was complete, it was up to the commissioners to get the work done. There was however one nagging problem, money. The Commission had been given a budget of $20,000 for their first two years, but with an acre of shoreline that featured beach front and a buildable upland area selling for $6,500, the money allotted would not go far.

None-the-less, with the coastal locations being given priority, the commissioners were able to act on a five acre, land-locked parcel that was being foreclosed upon on Sherwood Island in the town of Westport. By late summer they had finalized the deal and when, on December 22, 1914, the sale was recorded in the land records, the assembling of Connecticut’s State Park System was underway. Seven days later, as if fulfilling the desire of the failed 1909 attempt at preservation, the acquisition of 150 acres of Connecticut River frontage - Hurd State Park, East Hampton - including a dock for visitors, was recorded.

|

While Sherwood Island was the first purchase of land for the new park system in 1914, it did not have public access until 17 years later. Here the Park Commissioners are looking across New Creek into the park at illegal campers in 1923. |

Beside the first two acquisitions by the Park Commission, 1914 brought with it something else – a world at war. During the years 1914 to 1918 the Commission kept at its acquisitions but were in the fortunate position of having very few visitors; fortunate because providing for guests was a whole new entity best handled incrementally. By the end of the First World War in 1918, there were fifteen state parks. Scattered around the state, they preserved a variety of hilltops, small brooks and lower Connecticut River Valley lands. But this was not what Turner had envisioned. The Commission was now five years old and there was little preservation along the most quickly disappearing resource, the shoreline.

On December 10, 1918 Turner changed the course of park history. In no uncertain terms he told the Commission that the coastline park was a priority. The experiment in Westport had proved folly for public use, and it was now time to secure something substantial, improve it to a high level for guests, and then let the public decide if that was the direction the Commission should take in the future.

What happened as a result of that meeting remains the greatest accomplishment of the old State Park Commission. Within weeks the commissioners had secured hundreds of thousands of dollars for the project. Through midsummer and fall 1919, the first land purchases were underway. By early winter, plans were drawn up for a three-hundred foot long pavilion and lumber ordered. Property was purchased, water systems laid down, road grading completed, electric services installed and, in early spring, construction of the massive pavilion was underway. By late spring condemnation procedures were enacted for those land holders unwilling to cooperate and, on July 18, 1920, nineteen months after Turner 'inspired' the Commission, Hammonasset Beach State Park opened to the public. From that moment to this day, Hammonasset is the most visited park in the Connecticut State Park system. Turner was right, this was what the public wanted.

|

The first pavilion seen here at Hammonasset Beach State Park was constructed in the spring of 1920. It was 300 feet long and stood on over 1,000 piles, many of them dead chestnut trees brought in from Devils Hopyard State Park. |

|

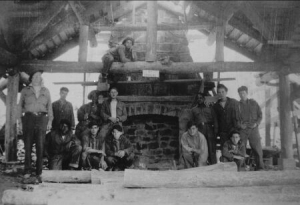

As the 1920s saw the transition from primarily rail and trolley traffic to primarily motorcar traffic, attendance figures soared in state parks. The long work lists and improvements to the ongoing acquisitions came to an end with the stock market crash in 1929. But it was with good fortune that much of that work, and more, would be completed by Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps during the decade of the 1930s. The CCC boys, as they were known, fulfilled the recreational dreams of all who envisioned life beyond the bad times. Miles of roadway were built providing access to park lands, dams were constructed to create swimming ponds, picnic shelters were erected and, in all, the CCCs impacted at least twenty-five state parks with improvements that would have otherwise taken years and cost the state millions of dollars. Their legacy is easily overlooked, but enjoyed daily by many thousands of visitors to the Connecticut State Park system.

|

The Civilian Conservation Corps Camp Roosevelt was constructed in 1933 in what is now Chatfield Hollow State Park. The C’s in this image built the picnic shelter overlooking the pond. Today only the massive stone chimney remains. |

The Second World War brought its own challenges to parks with deep cuts to staff and funding, along with commensurate huge reductions in visitation. But the post-war boom saw new growth in ways the founders may never have dreamed.

|

Crippling gas shortages and rationing during the Second World War caused an 86% reduction in visitation from earlier boom years. One work-around was making bicycles the vehicle of choice as seen here at Wharton Brook State Park. |

|

The fifty-one parks at the end of the war were on the threshold of what we recognize today as the modern park experience. Camping began to boom in the 1950s, the onset of very affordable photography brought many new users to the park, habits changed from day-long visits to hours-long visits, technology advancements in hiking and backpacking gear saw demands for good trails. And the park system continued to grow.

|

After World War II, public recreation in state parks put new demands on planning and staff. Temporary cabins were assembled in May and became the summer home away from home for many who otherwise would have had little or no access to the shore line. |

By the 1970s, about the time that the State Park and Forest Commission was winding down its run, before being incorporated into the new Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, parks found help from local benefactors. In 1970, the first of the local advocacy groups was instrumental in the preservation of Haley Farm in Groton, Connecticut. This set in motion a new chapter in park history just as an old chapter was closing.

On September 15, 1971, Meeting 676 of the State Park and Forest Commission, was held in New Haven, just a half mile and sixty-eight years removed from the first meeting in 1913. Talk had begun as early as the late 1950s to incorporate many state natural resource and outdoor recreation entities into one agency. With the onset of the environmental movement of the late 1960s and into the early 1970s, the day had dawned for a new way to manage resources under one roof. On October 1, 1971 the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection was formed, and among its many divisions, State Parks was one.

Since park employees had been state employees from the very beginning they continued as such, the leadership is what had changed. Instead of a volunteer Commission which met once a month, now there was Director of State Parks. But the recreational demands of the public were the same.

In addition to demands for recreation the public was increasingly vocal about the resources available for care of the parks. And from this timeless interest in the protection and maintenance of Connecticut’s wonderful resources came the onset of Friends of Connecticut State Parks. Although the umbrella group was created in 1994, many of the Friends groups around the state formed in the early 1980s. With their help in volunteer labor, education and finances the state parks system and the public has benefitted greatly.

|

The second half century of park history saw changes in visitor habits. Gone are the days of lounging in the 300 foot open pavilion on a day long visit to the shore, replaced by short visits of a few hours taken as busy schedules allow. |

|

Through the years acquisitions have continued, still solidly based around Albert Turner’s earliest precepts, especially having to do with waterfront, be it rivers, streams or shoreline. The perpetual expenses are met better at some times than at others, and so the ebb and flow of improvements and advancements continues.

100 years

As Parks has reached its 100th year anniversary, looking back provides an amazing perspective on the earliest days, the growth, the highs and lows, and the demands of the future.

As Parks has reached its 100th year anniversary, looking back provides an amazing perspective on the earliest days, the growth, the highs and lows, and the demands of the future.

Park attendance has stabilized at about 8 million visitors a year across the one-hundred seven State Parks. The system embraces a remarkable inventory of landscapes and water ways. It has grown to encompass a wide variety of historic locations that address a history older than the nation itself.

Tomorrow

With one-hundred years complete it is reasonable to look ahead and wonder what tomorrow will bring. In the earliest attempts to see into, and then plan for, tomorrow, Albert Turner wrote, “I tried to look ahead thirty years, and then still future thirties . . . “ , and that is what much of the planning mirrors today.

With one-hundred years complete it is reasonable to look ahead and wonder what tomorrow will bring. In the earliest attempts to see into, and then plan for, tomorrow, Albert Turner wrote, “I tried to look ahead thirty years, and then still future thirties . . . “ , and that is what much of the planning mirrors today.

What we know about tomorrow is that the waves will still meet the shoreline at the coast, the rivers will still pour over the waterfalls, the trees will bloom and lose their leaves, and the birds will arrive, nest, raise their young and depart. Invasive plants, animals and diseases will continue to upset today’s balance. There will be dry years and there will be wet years. Violent weather will impact every aspect of every acre at some time, and, new generations of families and friends will continue to come. They will reflect on the quiet of a pond, build sandcastles at the shore, swim in freshwater ponds, fish in quiet streams and picnic in wooded groves. They will enjoy the fruits of Mother Nature and the labor of park employees.

And the park lands will continue to open their gates to make every visit, by every person, at every location the best it can possibly be.

Content last updated July 2014