Tomato (Lycopersicon)

Plant Health Problems

Diseases caused by Fungi:

Damping-off, Rhizoctonia solani, Pythium sp.

Seedlings either rot and do not germinate or germinate and collapse. The disease frequently attacks the base of the seedling and leaves a shriveled, dried-up stem at the base of the seedling.

Control can be achieved by using sterile potting media, clean pots, and fungicide-treated seed. If seedlings in a seed tray become symptomatic, discard all of the seedlings since asymptomatic seedlings may be infected.

Root and crown rot, Rhizoctonia solani, Pythium sp., Fusarium sp.

Symptoms appear as wilting and a slow or rapid collapse of the plant. The roots can appear brown and water-soaked instead of white. A water-soaked lesion can often appear at the base of the stem.

Control can be achieved by using sterile potting media, clean pots, and fungicide-treated seed. Affected plants should be rogued out and discarded.

Verticillium wilt, Verticillium dahliae.

Symptoms of this disease resemble Fusarium wilt of tomato. Older leaves of diseased plants turn down, wilt, and become yellow. Other leaves follow suit, and the whole plant may be killed. If the plant survives it is usually stunted and the fruits are small, few, and of poor quality. Scraping the stem near the ground reveals a dark discoloration. The disease is caused by a soilborne fungus that persists in the soil for long periods.

This disease can be avoided in the greenhouse by soil pasteurization, and the use of resistant varieties. Both greenhouse and field types resistant to Verticillium wilt are available. Rotation with corn for at least two years may reduce inoculum densities. Fungicides are ineffective for control of this common disease.

Fusarium wilt, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici.

Older leaves of diseased plants turn down and become yellow. Other leaves follow suit, and the whole plant may be killed. If the plant survives it is usually stunted and the fruits are small, few, and of poor quality. Scraping the stem near the ground reveals a dark discoloration. The disease is caused by the fungus Fusarium which lives in the soil and infects plants through the roots. The fungus grows up through the roots into the stem. The fungus is favored by high soil moisture and warm temperatures. It may be particularly serious in greenhouse tomatoes. It has been found in Connecticut tomato fields, but is usually not too important outdoors.

This disease can be avoided in the greenhouse by soil pasteurization, and the use of resistant varieties. Both greenhouse and field types resistant to Fusarium wilt are available. Fungicides are ineffective for control of this common disease.

Botrytis blight, Botrytis cinerea.

Botrytis blight occurs on many different kinds of plants. On tomato the disease appears when plants are grown under conditions of high humidity as in a greenhouse. The disease appears as tan to brown spots on leaves that can be associated with a grayish mold colonizing the damaged area. Senescing flowers are particularly susceptible and frequently have papery spots on them. The fruit can also be affected and may develop small whitish concentric lesions on the fruit.

Botrytis blight can be suppressed by avoiding overhead irrigation and watering in the morning to allow time for leaves and flowers to dry. Proper plant spacing can improve air drainage and rapid leaf drying. Control can also be achieved with the use of fungicide sprays applied as soon as symptoms are visible. Among the compounds registered for use in Connecticut is thiophanate-methyl. Consult the label for dosage rates, safety precautions, and indoor use.

Late blight, Phytophthora infestans.

Leaf symptoms of late blight are irregular, dark, water-soaked areas, covered on the underside by the frosty-white spores of the fungus which causes the disease. Fruit infections show as peppery red-brown, firm areas, usually near the stem-end of the fruit. The discoloration is usually only skin-deep. In most years, late blight is not serious on tomatoes in Connecticut except on late-crop tomatoes. It is greatly feared, however, because of the rapidity with which it spreads, and may destroy whole crops. The spread of the fungus is favored by cool, wet nights and warm, humid days. The disease also attacks potatoes. The fungus carries over from season to season in potato cull piles, or in compost heaps containing old potato or tomato debris. See Potato for a more detailed discussion of this disease.

Ordinarily, spraying for late blight control would begin in the first part of August. The time to begin, however, is when there is a period of weather favorable to the fungus. Such a period may take place anytime during the growing season. Spraying may be stopped during hot, dry weather. Control can be difficult, but can be achieved with the use of fungicide sprays applied when symptoms first appear. Among the compounds registered for use in Connecticut is metalaxyl plus mancozeb. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Early blight, Alternaria solani.

The disease begins as circular, brown target-spots on the leaves. These spots are usually ringed with an irregular area of yellow. Infected leaves eventually turn yellow and fall off. In bush tomatoes the top and center leaves of the plants are most severely infected. Foliage infection usually takes place and becomes noticeable just when the first heavy set of fruit is starting to develop and ripen. Fruit infections are usually not numerous. They appear as brown target-spots, similar to those on the leaves. The main damage from early blight is the loss of much foliage. This foliage is needed to produce the food which goes into the developing fruit. This makes for small, poor-quality fruit. Loss of leaves also exposes developing fruit to the sun, resulting in sunscald. Early blight very often attacks seedlings in cold frames during periods of overcast skies and cold weather. Seedlings usually recover from the attack as soon as the skies clear.

Control can be achieved with the use of fungicide sprays applied when symptoms first appear. Among the compounds registered for use in Connecticut are chlorothalonil, mancozeb, and copper. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Anthracnose, Colletotrichum coccoides.

This disease appears as small, flat, circular, shiny, dark spots on the ripening or ripe fruit. These spots are fairly soft and serve as wounds for the entry of other rotting organisms which may destroy the whole fruit. The fungus causing this disease may infect the fruit anytime from the green stage until harvest. Because the symptoms are not prominent until the fruit ripens, many growers do not become concerned about anthracnose until it is too late to prevent infection. Anthracnose, like early blight, is both soil- and seedborne.

Use clean seed and practice crop rotation. To protect against anthracnose, spraying should start at the green-fruit stage. Control can be achieved with the use of fungicide sprays applied when symptoms first appear. Among the compounds registered for use in Connecticut are azoxystrobin, chlorothalonil, mancozeb, and copper. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Septoria leaf spot, Septoria lycosperisici.

The disease is caused by a fungus and first appears as small chlorotic spots on the older leaves. As the lesions enlarge, the spots become necrotic and a chlorotic halo develops around the lesion. Lesions can coalesce and eventually cause the leaf to drop off. The disease usually develops too late in Connecticut to cause much loss in yield.

However, if the disease becomes severe in July, compounds can be applied. Control can be achieved with the use of fungicide sprays applied when symptoms first appear. Among the compounds registered for use in Connecticut are azoxystrobin, chlorothalonil, mancozeb, and copper. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

For more information, see the fact sheet on Septoria Leaf Spot of Tomato.

Powdery mildew, Oidium sp.

The disease is relatively new to Connecticut, but it is common on many other plants. White powdery patches appear on the upper and lower surfaces of the leaves. These patches eventually coalesce and can cause leaf browning.

Control can be achieved with the use of fungicide sprays applied as soon as symptoms are visible. Among the compounds registered for use in Connecticut is sulfur. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

For more information, see the fact sheet on Powdery Mildew of Tomato.

Leaf mold, Fulvia fulva, Cladosporium fulvum.

The disease is caused by a fungus and appears first on lower leaves as pale green or yellowish areas with indefinite margins on the upper leaf surface. The fungus sporulates on the upper surface. The disease is most severe when humid conditions prevail, such as in a greenhouse.

Control can be achieved with the use of fungicide sprays applied as soon as symptoms are visible. Among the compounds registered for use in Connecticut are maneb and chlorothalonil. Consult the label for dosage rates, safety precautions, and indoor use.

Diseases caused by Bacteria:

Bacterial canker, Clavibacter michiganese.

The disease is caused by a bacterium which can be seedborne and soilborne. Symptoms appear as large cankers at the base of the plants which ultimately kill the plant.

There are no effective chemical controls for this disease. Symptomatic plants should be rogued out and discarded. Rotation out of tomatoes for two years may also provide some disease suppression.

Diseases caused by Viruses:

Mosaic diseases, several viruses. Mosaic-infected plants show leaf mottling which may vary from light green on dark green, to yellow on light green. The leaves may be very twisted and deformed. Narrow "shoestring" leaves are sometimes produced. Dead streaks occasionally show along the stems and petioles. The plants may show various degrees of stunting. Fruits are often small, knobby, misshapen, and may show mottling. Plants infected early in their development may be a total loss. Plants infected later in the season may produce an adequate crop if they are given extra fertilizer. Mosaic on tomatoes is caused by a number of viruses. Any virus may produce disease, either alone or with other viruses. The viruses which attack tomatoes also attack a great number of other crops and weeds such as tobacco, cucumber, pepper, ground-cherry, horse nettle and nightshade. Certain viruses may be spread by aphids or by handling infected plants first and then healthy plants. Infectious amounts of virus have been found in smoking and chewing tobacco.

To avoid mosaic, keep down weeds around tomato fields, control tomato insects, particularly aphids, and do not use tobacco when handling tomato plants. Remove and destroy mosaic-diseased plants from seedbeds and fields.

Diseases caused by Nematodes:

Root-knot nematodes, Meloidogyne sp. infected plants appear stunted and sickly. The fine roots are knotty, and have elongated overgrowths. This disease is caused by microscopic eelworms, called nematodes, which infest the soil. These nematodes invade the fine roots, feed on the plant juices, and lay their eggs within the tissues of the roots. This activity causes the plant to produce the root knots, and interferes with normal functioning of the infected roots. Eventually the roots decay, badly damaging the diseased plant, and release the nematodes into the soil.

To avoid the disease, start seedlings in sterilized soil. When buying transplants, examine the roots to make certain they show no root knots. Do not plant susceptible crops in an area with a past history of nematode root knot.

Diseases caused by Physiological/Environmental Factors:

Blossom-end rot, physiological.

Tomato varieties susceptible to this injury develop brown to black, irregular, sunken areas around the blossom-ends of the fruits. This is supposedly caused by a period of cool, wet weather during rapid fruit development, followed by hot, dry days. The injury is not caused by any microbe. It is apparently brought about by the foliage robbing water from the soft, rapidly developing fruit-end. This causes the robbed fruit tissue to dry and collapse.

Blossom-end rot can be avoided by mulching your plants and providing sufficient irrigation.

For more information, see the fact sheet on Blossom-End Rot of Tomato.

Internal browning, undetermined cause.

Tomato fruits with internal browning have grayish discolored blotches on the skin. When these fruits are cut, they show brown, collapsed spots in the wall and flesh. There is some question about the actual cause of internal browning. The latest information indicates that the symptoms are a "shock" reaction caused by infection of the plant with mosaic viruses just as the fruits are developing. The symptoms may appear on only one fruit of the set, or on one or more sets. Cold, wet weather favors the appearance of symptoms.

Warm, dry weather tends to prevent the symptoms. Fertilizing with high-potash fertilizers tends to reduce the disease. No fungicidal sprays will control internal browning. To reduce the chances of getting the disease, use the control measures suggested in the preceding section on mosaic diseases.

Growth cracks, environmental.

These circular, concentric rings appear around the stem-end of the fruit. They are not caused by any microbe, but are brought about by weather conditions, or poor fertilization practices. Growth cracks supposedly arise in the following way. Fruit growth slows down because of drought, cool weather, or lack of fertilizer. Suddenly there is a rainstorm, or warm weather, or the plants are side-dressed with extra fertilizer. Whatever the cause, the fruits start to grow more rapidly than their skins will allow, and the growth cracks appear. When the change in growth rate is too sudden, the fruits may actually split. Growth cracks and splits may serve as wounds for the entry of fungi and bacteria which may rot the injured fruit.

To avoid growth cracks and splitting, see to it that the plants get a fairly uniform supply of water and fertilizer.

2,4-D injury, environmental. Tomato plants which have been exposed to 2,4-D have twisted, downward-curled leaves, and zigzag stems. New growth of such plants is usually stunted and deformed. The youngest leaves appear pulled out of shape and show deformed veins. If a 2,4-D-injured plant produces fruits, they are usually small, oval, and seedless. Tomatoes are extremely sensitive to 2,4-D. The ester form of 2,4-D is particularly volatile and most likely to cause injury if used anywhere near tomatoes. The amine and salt forms are less volatile.

The best practice is not to use 2,4-D around such sensitive vegetables as tomatoes or beans. If 2,4-D is used, do not open the container or mix the spray near growing vegetables. Spray only on very quiet days, and keep the spray nozzles low. 2,4-D is very hard to clean out of a sprayer. If a sprayer is once used for 2,4-D, do not use it for applying anything to vegetable plants.

Leaf rolling, environmental. During the first hot days of summer the edges of the lower leaves often will roll upward. This upward leaf rolling is supposedly caused by sudden hot weather after a period of lush growth. The symptom is usually most prominent on staked tomatoes. Leaf rolling is temporary and causes no damage to the plant or crop.

Insect Problems:

Aphids.

The potato aphid and the green peach aphid both commonly infest tomato plants. See Aphid fact sheet.

Blister beetles.

Blister beetles.

In some seasons, large, slender, soft-bodied black or gray blister beetles may cause some damage by feeding on tomatoes. Control is not usually necessary.

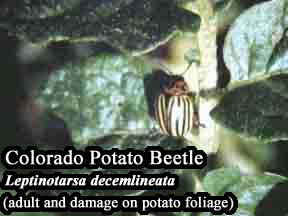

Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata.

Adults and larvae of the Colorado potato beetle occasionally feed on tomatoes. See Colorado potato beetle fact sheet.

Stalk borer, Papaipema nebris.

The eggs of this caterpillar are laid in the fall by the moths on surrounding grasses and weeds. After hatching in the spring the borers feed on these plants and later may migrate into adjacent tomato fields where they cause injury. The caterpillars are very active. Their restless habit of frequently changing from one plant stem to another increases the damage. Keeping the borders of the vegetable garden well-mowed and controlling weeds may help deny these insects their breeding grounds.

Cutworms.

Perhaps 14 or 15 species of moths, the larvae of which are called cutworms, feed on tomato. All belong to the family Noctuidae, and all are somber-colored moths. In most cases, the larvae feed at night and remain just below the soil surface during the day. Most of these cutworms reach a length of 1 to 2". They are smooth, robust, naked caterpillars, dull gray, greenish or brownish in color, indistinctly marked with spots and longitudinal stripes. Some have one generation each year and others have two or more, but most of those that are troublesome in the field are probably of the single-generation type that overwinter as partly grown larvae. Most of these commonly feed on grasses and weeds, but will feed upon a variety of plants when cultivation or other causes destroy their regular food supply. A few species are able to travel across large plowed fields to find food. See Cutworm fact sheet.

European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis.

This borer may occasionally attack tomato. Infestations usually occur when tomatoes are planted next to early corn and the borers migrate from the dying corn to the succulent tomato vines. The larva is pale white or gray with black tubercles and is not more than an inch in length when fully grown. Adults have a wing spread of an inch or so and are buff to brown in color. There are usually two generations annually. Eggs are laid on the undersides of leaves, and the larvae tunnel in the stalks and pupate in the burrows. Second-generation larvae and those of the single generation corn borer overwinter in the stalks and pupate in the spring.

Control begins with tillage of the corn stubble, either in the fall or early in the spring. This reduces the survival of borers from the previous year. Pheromone traps may be used to monitor flight of the adults.

The parasitic wasp Trichogramma has been used as for control. This tiny wasp attacks the egg masses of the corn borer, and the eggs of other caterpillars, too. Be sure to purchase the insects from a reputable supplier and make sure the strain you purchase is known to be well adapted to attacking corn borer. Several insecticides harm Trichogramma wasps, but not Bacillus thuringiensis.

Garden springtail, Bourletiella hortensis.

This tiny insect may injure young tomato seedlings. Small seedlings may be fed upon by minute, dark purple, yellow-spotted insects that eat small holes in the leaves. These insects have no wings but are equipped with forked, tail-like appendages by means of which they project themselves into the air. They are usually found only on small plants near the surface of the soil. Control is not usually necessary.

Potato flea beetle.

This small, black, active beetle feeds chiefly on the underside of the leaves and may damage the foliage. Injury is usually most severe to newly set plants early in the season. See the Flea beetle fact sheet.

Tomato fruitworm, Helicoverpa zea.

The tomato fruitworm, known as the corn earworm when it attacks corn, occasionally feeds on the fruit of tomato. The caterpillars are restless and frequently move from fruit to fruit, thus damaging many while not completely consuming a single one. The variegated cutworm, a species of climbing cutworm, may also attack the fruit in a similar manner. Among the compounds registered for control of this pest in Connecticut are Bacillus thuringiensis var kurstaki (Bt), Bt var aizawai, or carbaryl. These sprays must be present when the eggs hatch, because once the larvae are inside the fruit, they can not be reached with insecticides. Consult the label for dosage rates, safety precautions, and preharvest intervals.

Tomato hornworm, Manduca quinquemaculata.

Tomato hornworm, Manduca quinquemaculata.

The larvae of this insect and that of the tobacco hornworm often feed upon the leaves of tomato. When fully grown, this larva is about 4" long, green with oblique whitish bands along each side and a horn on the tail end of the body. The adult moth is similar to that of the tobacco hornworm except that the forewings have a mottled gray-brown, appearance, and are somewhat darker in color. The wing spread is between 4 and 5". Although these caterpillars become large and consume a substantial quantity of leaf material, they are rarely abundant enough to require more than handpicking on tomato in gardens. They do not usually feed directly on the fruit, and their abundant natural enemies usually regulate the population. Among the compounds registered for control of this pest in Connecticut are Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki (Bt) or rotenone, which must be used when larvae are still small. Handpicking is more effective in gardens when the larvae are larger and more obvious. Consult the label for dosage rates, safety precautions, and preharvest intervals.

Whiteflies.

The greenhouse whitefy, Trialeurodes vaporariorum, the sweetpotato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci, and silverleaf whitefly, Bemisia argentifolii, commonly infest tomato under glass, as well as many other kinds of plants, and are often carried into the field where they may persist on the plants. The life cycles of these species are similar. The tiny, white moth-like adult has a mealy appearance due to the small particles of wax that it secretes. It lays groups of eggs on the undersides of leaves. The eggs hatch into small oval crawlers, which then settle down and become scale-like nymphs that suck sap from stationary locations on the leaves. These then spend about 4 days in an immobile pupal stage before becoming adults. About 5 weeks are required to complete the life cycle in the greenhouse.

Yellow sticky traps are an effective way to monitor populations of whiteflies, and may even be attractive enough to reduce minor infestations.

Biological controls can be effective against whiteflies, especially in a greenhouse environment. The predatory ladybeetle Delphastus pusillus, specializes in whiteflies and feeds on all three whitefly species. The parasitoid, Encarsia formosa, can control the greenhouse whitefly in the greenhouse, but not the other species. Another parasitoid, Eretmocerus californicus, attacks all three species and can assist in controlling minor infestations in the greenhouse. Insecticidal soap or ultrafine horticultural oil, sprayed on the undersides of leaves, can be used against whiteflies in the greenhouse or the field. Azadiractin (neem) is registered for control of this pest in Connecticut. To be most effective, this material has to be directed to the undersides of the leaves. Repeat applications of sprays, a minimum of 7 days apart, will probably be needed because some stages in the life cycle are not affected by insecticides. At lower temperatures the insect develops at a slower rate and spray applications can be spaced further apart. Chemical control using conventional insecticides is difficult because of widespread insecticide resistance. Consult the label for dosage rates, safety precautions, and preharvest intervals.