Connecticut State Forests - Seedling Letterbox Series Clues for Quaddick State Forest

|

Quaddick State Forest -

|

|

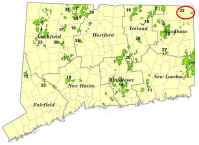

Quaddick State Forest contains approximately 550 acres and is located entirely in the town of Thompson in the extreme northeastern corner of Connecticut. It is bordered on the east by Rhode Island. The forest is located both on the east and west sides of the Quaddick Reservoir, an industrial reservoir covering approximately 466 acres. The original parcel was acquired by the Resettlement Administration of the United States government and leased to the State back in the 1930s.

The forest protects the reservoir while also providing ample recreational activities. This includes fishing for bass and pike; hunting for deer, turkey, and small game; canoeing and kayaking opportunities; and youth group camping.

Description: The letterbox lies off of Quaddick Town Farm Road in Thompson. The hike is approximately 1/2-mile in length roundtrip, on easy terrain. The estimated roundtrip time is 45 minutes. A compass is helpful for bearings. Wearing bright orange is encouraged during hunting season (mid-September through December). Mosquitoes and deer flies can be thick by the wet areas, so consider bringing insect repellent.

Clues: To access the Quaddick State Forest Letterbox, take Exit 99 off of Interstate 395 (Route 200/North Grosvenor Dale/Thompson Exit). Go east on Route 200 for approximately 0.6 miles until you reach a four-way intersection (Junction of Route 193). Go straight through the intersection and follow Quaddick Road for 2.6 miles. At the stop sign, turn left onto Quaddick Town Farm Road. Follow for 2.4 miles to intersection with Baker Road. Continue straight for 0.1 mile past Baker Road.

The start of your letterbox hike begins at the cedar gate on the left side of the road. Park in front of the gate, or back at the junction of Baker Road, on the dirt portion of the road. Beware of large trucks travelling at high speeds on Quaddick Town Farm Road.

Walk through the gate and look to the left into an old plantation of red pine. Red pine is a conifer, otherwise known as an evergreen – it keeps its needles year round. It has 2 needles per fascicle (cluster), and reddish, plated bark. Notice how tall and straight the red pine grows. This quality makes red pine a desirable species for utility poles.

Can you guess how old these trees are? Do you see any signs of management? To get a feel for how fast a plantation can grow, take into consideration that these trees were planted in the 1950s, thinned for pulpwood in 1973, and thinned for sawlogs in 1983. The term “thinning” refers to removing lesser quality trees to reduce overcrowding and promote growth in residual trees. The last management done in this plantation was in 1983, when fifty 65-foot trees were harvested for use as utility poles. No management has been done since then because there has not been a forester assigned to the Quaddick State Forest for over 25 years.

Red pine is not native to Connecticut and, in most cases, was planted in plantations like this. During the 1990s and 2000s, most stands of red pine were killed by exotic insects, such as the red pine scale and/or the red pine adelgid or have been salvage harvested for their wood products. Some of the trees in this stand may still be alive, perhaps because the past harvest operations allowed enough space between trees to limit the spread of the insects. Or, it may be because this area of red pine is separated enough from other infected areas of red pine so as not to be affected.

As you start walking along the old woods’ road, you will pass numerous brush piles. Notice about 200 feet down the road, the trees close in on either side of you. This regeneration consists primarily of white pine with some scattered oak. White pine is different from red pine in that it has five needles per fascicle instead of two. Looking beyond the regeneration on the right side of the road, you will see a few large white pine trees. This stand of trees was heavily thinned in the early 1980s. The State-run crew harvested much of the mature white pine, and sent the wood to the state-run sawmill. The lumber from these trees was used for picnic tables and buildings that can be found at the various state park and forest facilities. Other wood was sent to the state-run shingle mill in Voluntown to produce shingles. Notice how tall the regeneration has grown in the past 35 years. Now would be a good time to go back to harvest the overstory trees to release this regeneration, and allow it to grow with more sunlight.

At 350 feet, stop at the opening for the wildlife marsh on your right. This man-made emergent marsh, called Sherman Marsh, was created in the early 1950s as goose and duck habitat. At that time, it was a fairly open body of water, but as you can see it has grown in over the years. As the marsh fills in, it loses some of its original value for geese and ducks, but increases in value for other species, such as frogs and turtles.

As you follow the road across the dam structure, notice the hardwood wetlands on the left side of the road. Many common wetland plant species are found here, such as skunk cabbage, pepperbush, and multiple types of ferns. Skunk cabbage is one of the first plants to emerge from the ground in the spring and is well known for its ill scent and ability to produce its own heat. It can literally melt its way out of the ground! The flowers of skunk cabbage are purplish-brown and green, and the plant flowers between February and April. The broad spreading leaves arrive after the flower and reach a height of 1-2 feet.

Sweet pepperbush is a deciduous woody shrub reaching 3-10 feet in height, also found near wetlands. It has shiny, alternate leaves with toothed margins and a short stalk. The fragrant white flowers, located on a spike poking above the shrub, bloom in midsummer. These white flowers bloom from the bottom up so that the oldest flowers are on the bottom.

Can you see a skunk cabbage plant or a sweet pepperbush here?

Where the marsh separates from the road briefly, look left to see an old stone wall and unofficial trail heading south/southwest. From this point, head south-southwest for approximately 225 feet, following the stone wall and unofficial wooded trail until you see a large rock on your right and the trail bends to the right. The trail can be followed by passing in front of two downed trees covered in moss. As you walk the section just mentioned, you will notice the drier, uphill site that is home to plant and tree species different from those you were just viewing in the wetlands. This stand you see now is a small, sawtimber-sized white pine stand. Not a lot of light is reaching the forest floor in this area due to the crowded conditions of the trees. As a result, there are very few understory species found here, with mostly just pine needles carpeting the forest floor. As you continue walking, the bigger white pine trees will give way to smaller pole timber trees. You will notice that there is lot of white pine in the understory in this area. This is a good time to familiarize yourself with white pine. As you enter the regeneration area, look closely at a seedling or sapling on the left side of the trail. Count how many needles are in each cluster, or fascicle, as they are called. Can you guess the approximate age of the tree you are looking at? The age of a white pine can be easily determined by counting the “whorls” of branches, or cluster of branches, that grow out of the main stem forming a circle around the main stem. The space between these sets of whorls represents one year’s growth!

From the space between whorls you can also tell how productive a growing season the pine had that year - the longer the distance between whorls, the better the growing season! The trees in this area are probably around 25 years old and came in shortly after the red pine harvest mentioned earlier.

You will pass through the sawtimber red pine/white pine regeneration area and into an area where the regeneration thins out and there is mostly sawtimber-sized white pine overhead. Here, there is also a fern understory, which may not be visible in winter. This change occurs in a dip in the landscape that has a subtle difference in soil types, and is slightly wetter than the area you just came from. Did you notice the change?

At approximately 250 feet, you will cross another faint trail running perpendicular to the trail you are on. From this point, continue down the hill for 150 feet, passing through a mature white pine stand with an understory of white pine and fern.

You will then find yourself between two large white pine trees, the one on the left being larger than the one on the right. You will know you are at the right location if there is a large, old borrow pit off to your left (south) less than 100 feet away. A borrow pit is an excavated area where material has been dug for us at another location. Most likely, gravel or sand was dug out of this pit. From this point, continue to head southwest, crossing through a carved notch in a large downed white pine tree at 50 feet, and then climbing slightly to a knob another 100 feet beyond the downed tree. At this point, the understory opens in front of you, and the lake is visible through the trees.

As the understory opens, the forest floor will be primarily covered with both huckleberry and blueberry bushes. Blueberries are spreading shrubs, with leathery, unlobed leaves and white bell-like flowers that become blueberries. Huckleberries closely resemble blueberries but have darker and smoother bark and yellowish resin dots on the leaves. Huckleberry flowers can be either white or pink, and hang down in clusters. Both species like acidic soils and are important food sources for wildlife. They also both flower in early summer and fruit in mid- to late summer.

As you look around you, take into account that the stand of trees you are walking through was last cut in the late 1970s. The harvest was aimed at converting the stand from a softwood/hardwood stand of oak and pine to one that was primarily white pine. Did the planners succeed?

From the knob on the side hill where you now stand, continue downhill approximately 140 feet through a small patch of white pine saplings to the next hilltop knoll. On this knoll, the hilly terrain of the surrounding area becomes more noticeable. These steep slopes consist of gravelly sandy loams, which favor the oak pine forest types you see around you, including the blueberry/huckleberry understory. Pines are more suited to this type of soils, which explains the past desire to convert to pine.

From this point, the letterbox is located 50 feet to the north-northwest. If you are facing the water, turn right or head towards 3 o’clock. It is hidden under some rocks that are in between two mid-sized white oak trees. These oak trees have a group of dead or declining sapling-sized white pine closely located next to them. Alternatively, if you cannot find the letterbox; from the knob walk downhill towards the water until you reach a path. Turn north (right) and walk less than 100 feet and look uphill to see two trees with rocks in between sheltering the letterbox. After signing in, please replace the box where it was found, hiding it well to avoid vandalism problems.

If you have time to explore, head down to the water’s edge. Look for the flowering water lily pads if it is summertime, and listen for waterfowl year round. On certain summer or fall days, you may hear the Thompson Speedway Motorsports Park located at the top of the Reservoir. At the water’s edge, look back towards the way you came to see an 18-inch white pine with wildlife holes in it. Notice the sawdust at the bottom of the tree, indicating a large amount of rot inside the tree.

Learn More, Earn a Patch: This is one of 32 letterbox hikes that are being sponsored by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection’s Division of Forestry. When you have completed 5 of these sponsored letterbox hikes, you are eligible to earn a commemorative State Forest Centennial patch. When you have completed five of these hikes, please contact us and let us know what sites you have visited, what your stamp looks like and how we may send you your patch. We will verify your visits and send the patch along to you. Contact DEEP.Forestry@ct.gov.

Content last updated December 2024