The Spongy Moth: Outbreaks and Natural History

Outbreak Status

Of Mice and Moths

The Maimaiga Fungus

2016, 2017, and 2018

The spongy moth (formerly known as the gypsy moth) first came to North America around 1868. Its natural range is in Eurasia. In Europe, the moth has been known to be a problem since at least the 1600s. Here in North America, it has found a niche and is established in the northeastern parts of the United States and adjacent parts of Canada. It continues to spread west and south - states such as Minnesota have ongoing programs that seek to prevent the insect from invading their woods.

However, this is a battle that Connecticut lost in the 1910s and 1920s, after it was first found in Stonington in 1905.

Outbreak Status

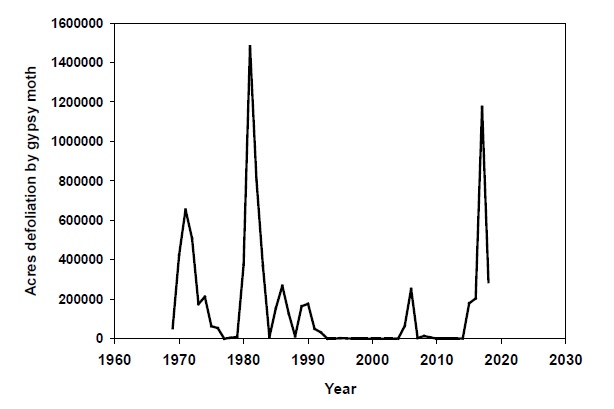

Chart prepared by the CT Agricultural Experiment Station (Note: The gypsy moth has been renamed the spongy moth.)

If the spongy moth stayed at low population levels, it would be of little more than passing note among naturalists. At low population levels, natural controls work to keep the spongy moth population in check. This includes a range of predators and parasites. Wasps parasitize the egg masses, while beetles, birds and mammals consume each of the various spongy moth life stages. Diseases such as that caused by the nuclear polyhedrosis virus (NPV) are also a factor.

However, the spongy moth has the ability to go into outbreak mode at regular intervals. In Connecticut, 1971 and 1981 are remembered as particularly bad years. In 1971, defoliation topped 650,000 acres, while in 1981, that number reached 1.5 million acres. That is nearly 80% of the state's 1.9 million acres of forestland.

Of Mice and Moths - Prior to 1989

White-footed mice eating larvae.

It is not known for certain why the spongy moth goes into outbreak mode. One hypothesis ties the start of an outbreak to a low year of mast production. "Mast" refers to the accumulated seeds of forest trees, such as acorns, beech nuts, and hickory nuts. In the forest, mast is the primary food for a variety of wildlife, including white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus). When the spongy moth population is at a reduced level, these mice are able to keep the moth population down by feeding on a proportion of larvae and pupae. While this feeding by the mice helps keep the spongy moths in check, it does not substantially influence the number of white-footed mice, as the spongy moth is not a critical food source for the mice.

The amount of mast available in the forest is more important in regulating the mouse population. When the mast crop declines, the mouse population also drops in number. When this happens, the spongy moth population, freed from being consumed by mice, begins to increase in numbers.

Because spongy moths are not a favorite food, the rise in the spongy moth population does not necessarily translate into an increase in the number of mice. Once the spongy moth population gets past a point at which mice are able to keep them in check, the growth of the spongy moth population tends to accelerate, until it achieves outbreak status.

The pattern of collapse of the spongy moth population on the other end of an outbreak is better known. At low moth population levels, a virus (NPV) is often persistent within the population, also at low levels. After the moth population reaches outbreak status, the NPV virus tends to spread widely within the moth population. However, there is usually a lag of 2 or 3 years to this occurring. Once NPV catches up with the moth population, it infects and kills moths in great numbers. This infection occurs during the caterpillar stage. It is this epidemic of NPV that, for most of the history of the spongy moth in North America, has caused the spongy moth population to collapse.

Since 1989 - The Maimaiga Fungus

Most of these caterpillars are dead, killed by the maimaiga fungus.

The emergence of the maimaiga fungus (Entomophaga maimaiga) in 1989 changed this dynamic greatly. This fungus is originally from Japan. It was released several times in the U.S. as a potential biological control agent, going back to 1910. After each trial, its effects on spongy moths appeared to be minimal. That is, until 1989. In that year, to the surprise of everyone, this fungus emerged from oblivion and immediately began killing spongy moth larvae on a wide scale.

The first known occurrence of this happening was in Connecticut. The spring of 1989 was exceptionally wet in the state. Since that year, in Connecticut, the fungus has re-emerged each year on its own, proving that it is able to sustain itself in the wild.

The maimaiga fungus is effective against spongy moth caterpillars because the annual life cycles of the two organisms interconnect very well. The maimaiga fungus persists in the soil and leaf litter as a resting spore. In the spring, when there is an adequate amount of rain, humidity in the soil and leaf litter activates the fungus.

As it turns out, starting around the 3rd instar, spongy moth caterpillars spend a significant amount of time on the ground, as they seek shelter during the hotter parts of the day. When these larger caterpillars begin descending to the ground, these activated spores have no problem finding and infesting them.

After being infested with the maimaiga fungus, a certain number of the caterpillars begin to climb back up a tree before succumbing to the fungus. From this perch, as the dead caterpillars decompose, the fungus releases a second, wind-borne type of spore that spreads the disease even further among the surrounding spongy moth caterpillars. Once it gets going, the fungus tends to move quickly through the population. (See a video of the fungus in action.)

At the end of the spongy moth season, the fungus produces a resting spore that then accumulates in the soil and leaf litter, to await the next year. These resting spores have been shown to remain viable in the soil and leaf litter for at least 10 years.

This cycle of infection by the maimaiga fungus has kept the spongy moth population in Connecticut at a low level for the past two-and-half decades. Each time the population of the insect began to grow, this fungus has managed to prevent it from becoming anything more than a localized outbreak.

That is, until a recent drought.

The Situation in 2016, 2017, and 2018 - What Happened?

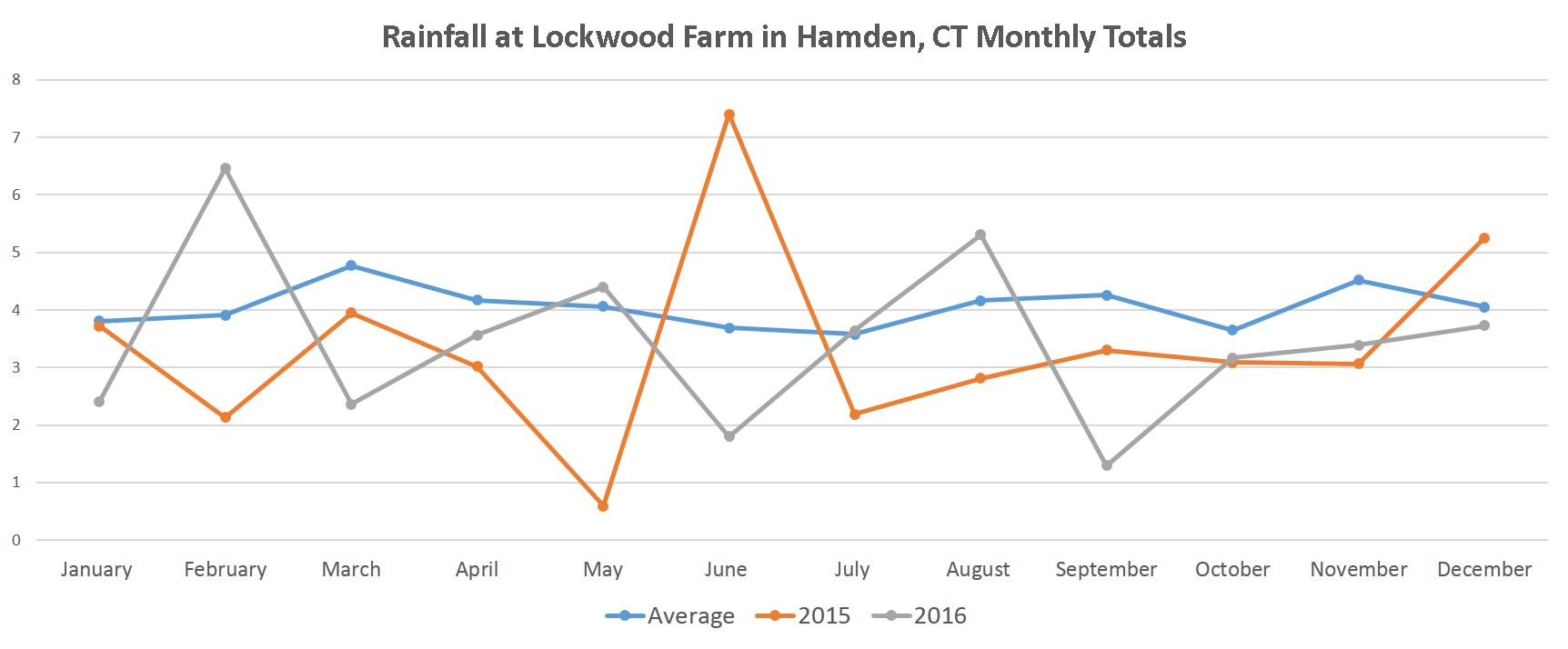

Note that rainfall for the spring months is below average in both 2015 and 2016.

Chart created using data collected by the CT Agricultural Experiment Station.

Much of Connecticut suffered under drought conditions in 2015 and 2016. At the same time, the number of localized spongy moth outbreaks increased and began to spread. This increase is attributed to the maimaiga fungus not being activated. In 2017, the spring was wetter than in the previous two years. These spring rains led to the maimaiga fungus being activated. However, the activation of the fungus was later in the season than expected. The slow activation of the fungus allowed the spongy moth caterpillars to survive well into the early summer. Areas in eastern Connecticut suffered extensive defoliation. (See the CT Agricultural Experiment Station's Spongy Moth Fact Sheet for further details.)

While the number of spongy moth egg masses counted by the CT Agricultural Experiment Station at the end of the 2017 season were down from the previous year, significant oak mortality continued into 2018 due to the one-two punch of defoliation and the drought having significantly weakened the trees. This set them up for further damage and even death from secondary pests and pathogens, such as the two-lined chestnut borer and the armillaria fungus. Oak mortality from these secondary pathogens continued on into 2019 and 2020.

There is one other aspect of the forest mast, mice, and spongy moth story that deserves mention. White-footed mice are known to be a main reservoir for the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. While the number of spongy moth larvae or pupae tend not to affect the mice population directly, the spongy moth does tend to influence how well the oaks and other forest trees produce their seed crops. A sufficiently large outbreak of the spongy moth can lead to a decreased forest mast crop in subsequent years, which will then lead to a decrease in the number of deer mice in the forest. As a result, spongy moth outbreaks have been associated with declines in the number of local cases of Lyme disease.

Additional Information

The Spongy Moth in Connecticut: An Overview

Information for Tree and Woodland Owners

A Brief History of the Spongy Moth

Contents last updated in March 2022.