Birth of the Eagle: How a Nazi training ship found its way to the Coast Guard Academy

The Day

By: John Ruddy

July 10, 2021

|

|

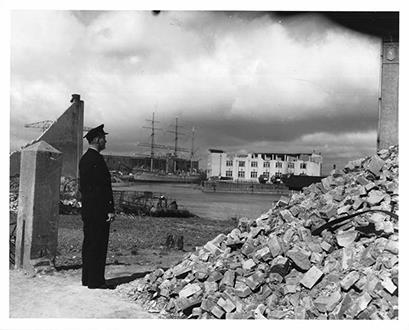

| The German navel training ship Horst Wessel sits amid the ruins of Bremerhaven, where it had been towed at the end of World War II. It was refurbished there and commissioned by the Coast Guard as the Eagle before leaving for the United States in 1941. (Courtesy of the United States Coast Guard Historian) |

Cmdr. Gordon McGowan, right, the first captain of the Eagle, developed a friendship with Bertold Schnibbe, center, the last captain of the Horst Wessel, while the ship was being overhauled in Bremerhaven in 1946. The man at left is unidentified. (Courtesy of the United States Coast Guard Historian) |

Editor's note: This account is drawn from the books "The Skipper and the Eagle" by Gordon McGowan and "The Barque of Saviors" by Russell Drumm" and the archives of The Day.

The three-masted vessel that appeared in the harbor the morning of July 12, 1946, looked like something out of New London's past, but it belonged to the future.

Nearly 300 feet long with a graceful steel hull painted white, it was rigged as a barque: square sails on the foremast and mainmast, fore and aft sails on the mizzen mast. The ship docked at Fort Trumbull and was later inspected by 1,200 curious people.

Seventy-five years ago this week, New London got a first look at what would become one of its enduring symbols: the Coast Guard barque Eagle.

The arrival fit a pattern of events that defined 1946: the tying up of loose ends from World War II. The U.S. Maritime Service Officers School at Fort Trumbull graduated its final class and closed. Electric Boat launched its last submarines from wartime contracts. EB's shuttered Victory Yard was sold to a pharmaceutical company called Pfizer.

At the Coast Guard Academy, there was also unfinished business. During the war, 5,000 cadets had had the unusual chance to learn on a square-rigger. The training ship Danmark, in American waters when the Nazis invaded its home country, offered the U.S. its services and was assigned to the academy. Danmark had since departed, but officials learned a replacement was available in the ruins of Germany.

Here's how a ship built by the Third Reich found its way to New London to become a mainstay of the Coast Guard.

Cmdr. Gordon McGowan taught seamanship at the academy, but by his own account, his square-rigger expertise was limited. He had spent his early years in the service on a destroyer during Prohibition.

So he was delighted when he got orders in early 1946 to fly to Bremerhaven in occupied Germany, take command of a naval training ship and sail it back. The allies were dividing up the German fleet, and the U.S. had claimed the ship as a war prize.

McGowan may not have been fully qualified for the assignment, but he knew more than most anyone else at hand.

"The reasoning that 'In a village of blind men, a one-eyed man is king,' must have guided the ones who wrote my orders," McGowan later wrote. "I was the Coast Guard's one-eyed man."

In Bremerhaven, McGowan saw a city reduced to rubble by allied bombs. At a destroyed shipyard, he found what he was looking for. Resting on the bottom of the Weser River at low tide, its hull stained and blistered, was the training ship Horst Wessel.

It looked abandoned, but when McGowan went aboard, he found the German crew living there. With no orders and no destination, they were serving in a navy that no longer existed.

Ten years earlier, amid Third Reich pomp at the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg, their ship was christened with champagne by Bertha Wessel, its namesake's mother.

Even in the Nazi era, "Horst Wessel" was an unusual name for a ship. Most vessels honored German naval heroes of ages past, but Wessel had been a follower of Adolf Hitler who composed the Nazi anthem. At age 22, he was murdered by his girlfriend's ex-lover, but propaganda turned the squalid incident into a martyr's death.

"This ship shall bear the name of the fighter and poet at the forefront of the German revolution," Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess said at the christening as Hitler listened behind him.

Horst Wessel was the second of three square-riggers built for the sail-training fleet after a 1932 disaster in which the school ship Niobe capsized in a storm, killing 69 people.

War halted Horst Wessel's mission of sailing the North Atlantic. For a few years the barque was used to train members of the Marine Hitler Youth before being reactivated as a naval vessel late in the war.

In April 1945, packed with refugees, the ship headed west along Germany's Baltic Sea coast, away from the advancing Soviet army. It was intercepted by a British prize crew and disarmed. After Germany's surrender, its flag was hauled down.

As the allied navies haggled over the spoils of war, Horst Wessel was towed to Bremerhaven to await its fate.

McGowan didn't become captain immediately. For the moment, Horst Wessel was still under the nominal command of Bertold Schnibbe, a tall, thin 35-year-old whose crew addressed him affectionately as "Ka-Leut," a diminutive of his rank, Kapitän-Leutnant.

Wondering how military men of a defeated nation would treat him, McGowan was surprised to find Schnibbe showing respect and friendliness to his successor and crewmen snapping to attention whenever he appeared.

Schnibbe explained that the German navy had considered itself a professional fighting force largely without Nazi fanaticism. Still, by Hitler's order, the ship had been equipped with a demolition charge and was to be blown up if faced with surrender. After Hitler's death, the order was rescinded.

Awed by the ship's complex rigging, McGowan faced a big job making it seaworthy. Everything he needed — sail cloth, lines, paint — was hard to find, and supply officers kept directing his men to warehouses across Germany that were nothing but four roofless walls. A replacement engine block turned out to be the wrong model even though it had been researched down to the serial number.

The overhaul took months, but there was a bigger challenge. McGowan had 50 Coast Guardsmen at his disposal, 250 fewer than he needed to fully man the ship. But no others were available. So he cooked up a scheme to "borrow" some German ex-navy volunteers from a British minesweeping project, plus Horst Wessel's crew, to bolster the ranks.

The vessel's new name was to be "Eagle," which had a long Coast Guard pedigree. But when McGowan gave Schnibbe the news, the German chuckled and placed his hands a foot apart.

"Igel?" he asked. "In German that word means little animal, what you call 'groundhog.'" McGowan explained that "eagle" was English for "Adler." Comprehending, Schnibble said, "That is a fine name, Captain. It could not be better."

The new name also matched the ship's figurehead. The shipyard doing the repairs presented the crew with a piece of teak hand-carved into a shield to replace the swastika the wooden eagle clutched in its talons.

On May 15, 1946, Eagle became a commissioned Coast Guard vessel in a shipboard ceremony. With McGowan now in command, he dreaded having to ask Schnibbe to vacate the captain's quarters. But the German had moved to a different stateroom on his own.

When McGowan sought him there to thank him, "his head was on the desk, his arms outstretched. His shoulders were shaking silently. Seeing that he had not noticed my intrusion, I tiptoed quietly away."

On sailing day McGowan faced an unpleasant task. A boy named Eddie, orphaned by the war, had latched onto the crew. Showing military bearing and speaking perfect English, he endeared himself and was clearly angling for a ticket to the U.S.

Knowing he should have discouraged the attachment, McGowan sternly ordered the crew to produce Eddie, who had vanished, probably intending to reappear as a stowaway once the ship was at sea.

"It took about half an hour, but they dragged him, kicking and biting, to the ship's side," McGowan wrote. "Reproachful looks were aimed in my direction as they lowered him gently over the side."

After a stop in Falmouth, England, Eagle headed into open ocean, visiting two Atlantic paradises: Madeira and Bermuda. With most of the distance behind them and the crew having faced few problems, the journey seemed charmed.

But McGowan had a nagging feeling he had overlooked something. Two days from New York, he decided the weather was suspect but let himself be talked out of changing course. When he awoke in the night to the sound of wind, he knew he had made a mistake. Eagle was soon in the midst of a hurricane.

"The voice of the storm was more than a roar," McGowan wrote. "There was the sharp tearing sound — the ripping of the fabric of the gates of hell. ... The fore upper and lower tops'ls were the first to go. One moment they were there; a second later they had vanished." In all, $20,000 worth of sails popped like balloons.

Amid towering seas and 80-knot wind, McGowan struggled to heave to and let Eagle ride out the storm. He accomplished the difficult maneuver, and the ship survived.

Battered but triumphant, Eagle sailed to New York, dropped off the Germans at a POW camp, then proceeded to its new home in New London.

"Our initiation had been a severe one," McGowan wrote. "... I had my proof that a square-rigged sailing ship is a good place for a greenhorn to get his introduction to the sea."

Click here to view this article as it originally appeared on The Day website.