First Seven Submarines Arrived In Groton A Century Ago

By John Ruddy

New London Day

October 18, 2015

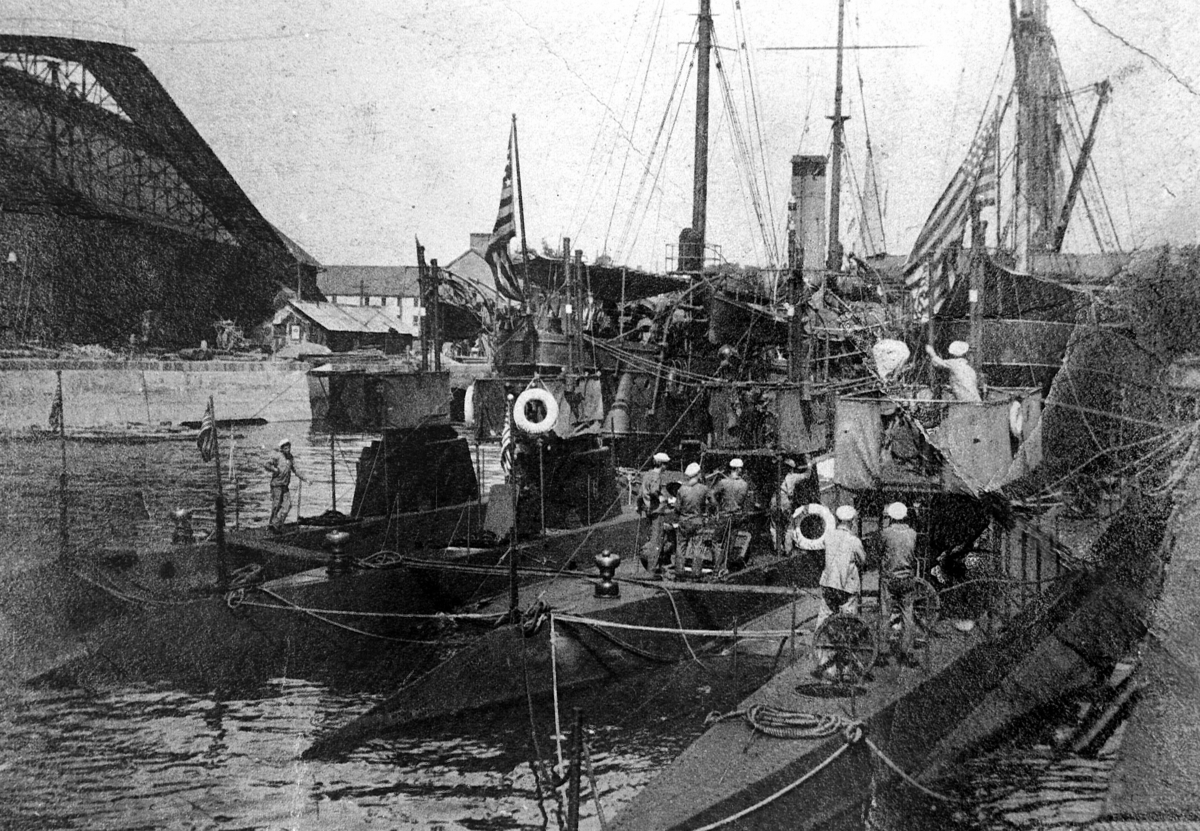

These D and G class submarines were among the first seven to arrive in Groton on Oct. 18,

1915, marking the beginning of the Naval Submarine Base. Credit: U.S. Navy - Submarine

Force Museum

The crowds lining both banks of the Thames River had seen plenty of ships entering New London Harbor, but never anything quite like this.

The seven vessels moving slowly upriver were not whalers, ferries, yachts, steamers or anything else most people would recognize as ships.

They didn't have sails or rigging or funnels, just smallish, slender hulls that barely broke the surface, each with a nondescript structure amidships.

On Oct. 18, 1915 – 100 years ago today – the first submarines arrived in Groton. They brought the future, setting in motion a century that would transform a quiet coastal town into the Submarine Capital of the World.

No one back then could see the future, but the coming of the strange little vessels was still a surprising and welcome development. How it came about involved a combination of politics, war and luck.

The New London Navy Yard in Groton, where the seven subs were headed, had been a place of no particular importance since its establishment almost 50 years earlier.

The Navy seemed to have no idea what to do with the place, and for years at a time, nothing happened there. It was inevitable that the yard would one day become the target of budget cuts.

When that happened, in 1911, something was finally going on there. The Marine Corps had just established a training school for officers.

That brought fewer than 100 Marines to Groton and only for the summer months. Still, as The Day noted, "The navy yard is on the map again."

The Virginia-class, fast attack submarine USS California (SSN 781) makes its way up the

Thames River returning to U.S. Naval Submarine Base New London from deployment Friday

Oct. 16, 2015. The California's return coincides with the 100th anniversary of the first

submarines to arrive in Groton. (Tim Cook/The Day)

But when a naval appropriations bill reached Congress in February 1911, the yard was on the chopping block, along with surplus properties in such far-flung places as Port Royal, S.C., Sacketts Harbor, N.Y., and Culebra, Puerto Rico.

Republican Edwin W. Higgins of Norwich, southeastern Connecticut's congressman, needed an argument that the yard didn't belong on the list.

He had the Marine Corps school, plus the yard's other current activity, a coaling station. He also had the fact that the property could not be sold. Under the terms of its establishment, it would revert to the state of Connecticut if abandoned by the Navy.

But Higgins instead argued something bolder: that the secretary of the Navy, who recommended the yard's disposal, had no idea how valuable it was. In a recent hearing, the secretary had said, "No vessel of any size can go in there."

Higgins told the House Committee on Naval Affairs that in fact the New London Navy Yard lay north of one of the best harbors on the East Coast; that the water was deep enough for any Navy vessel; and that the two largest ships in the entire world, the steamers Minnesota and Dakota, had recently been built in Groton.

He was persuasive, and the yard was removed from the bill. But shortly afterward, the Marine Corps school was transferred to Philadelphia.

The next year, the yard was again targeted for closure, and this time the naval affairs committee endorsed the idea. Higgins would have to appeal to the entire House to save it.

He told his fellow congressmen that abandoning the yard would break faith with Connecticut, which had donated the land. But perhaps more compellingly, he argued that the yard would be crucial in the event of a wartime attack on New York City.

Military strategists had envisioned such an attack coming via Long Island Sound, the eastern end of which had long been undefended. As a result, a chain of coastal fortifications were built in the 1890s, the largest of them on Fishers Island and Plum Island.

Higgins argued that the coaling station in Groton – the only facility of its kind between Brooklyn and Newport – played a key support role in national defense.

"In the event of war any fleet protecting New York from the east would rendezvous at New London harbor, which can float the navies of the world," he said.

On May 27, 1912, after making his case to the House, Higgins sent a telegram to The Day: "I was able to get provision abolishing New London navy yard knocked out of the naval bill today."

The same day, he made another announcement. After serving eight years in the House and twice saving the Navy yard, he would retire from Congress. He was 37 years old.

Higgins' successor was an even more zealous defender of the yard. Democrat Bryan F. Mahan was the can-do mayor of New London who, doubling as a state senator, had persuaded the legislature to appropriate the fabulous sum of $1 million for a steamship terminal. It's known today as State Pier.

When, early in his term in Congress, the yard was again threatened, Mahan fought the proposal in committee and fended it off as Higgins had before him.

But he didn't stop there. He introduced a bill to create a plant in Groton that would make armor plates for Navy ships. He also regularly harangued the secretary of the Navy about the yard's advantages.

It was Mahan who, while still mayor, had put out an appeal to the state's congressmen when the yard was threatened in 1912. He pointed out the site's potential wartime role, which Higgins then argued successfully before the House.

When war came in 1914, the idea still had currency. That year, former Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, writing in Harper's Weekly, imagined an enemy landing 150,000 troops in New London as the first stage of an assault on New York.

But the threat that transformed the Navy yard was directed not at New York but at American ships and travelers on the high seas, who were falling prey to German U-boats.

The first use of submarines in war was proving deadly against both military and civilian ships. Germany at first targeted the British navy, then merchant vessels, and finally, in early 1915, any ship that might be in British waters. Unrestricted submarine warfare had begun.

Neutral nations were put on notice that their ships were at risk. In May the liner Lusitania was torpedoed off Ireland, killing 1,198 people, including 128 Americans. The incident threatened to drag the U.S. into the war.

American submarines were not yet a fighting force and didn't even have a base of operations. Tenders or mother ships served as floating bases and were manned by four times as many sailors as the subs themselves.

The new secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, had abandoned his predecessor's push to dispose of surplus properties and was finding new uses for them.

In August 1915, perhaps with Mahan's persistent appeals on his mind, Daniels sent Capt. Albert W. Grant, commander of the Navy's Submarine Flotilla, to Groton to gauge the yard's suitability as a submarine station on shore in place of tenders.

When Grant reported back favorably, Daniels went to have a look for himself.

Days before his arrival, he got an unwelcome reminder that submarines were the future of naval warfare. A U-boat torpedoed the U.S.-bound liner Arabic, with the loss of 44 lives, including three Americans.

In Groton, Daniels didn't find much to look at. The abandoned yard included the old Marine barracks and a few other buildings. The population consisted of a caretaker and any number of rats.

But the 90-acre property with a mile and a half of waterfront was ideally located. Downriver, in addition to the deepwater port, was the New London Ship & Engine Co., which built submarine engines for the Electric Boat Co.

In nearby Bridgeport was the Lake Torpedo Boat Co., which built submarines for the Navy.

After his tour, Daniels made the yard's new role official with an announcement to the newspapers. Then he stopped in New London and walked up State Street to the post office.

The postmaster was Bryan Mahan, who had lost his bid for re-election.

"You see," the secretary told him, "I have kept my promise. If you remember, I told you the first opportunity that transpired for the development of the New London station would receive my careful attention. And after the lapse of two years, here I am, prepared to make good."

Less than two months later, seven submarines set out from Newport, R.I., for their new home in Groton.

The D-1, D-2, D-3, E-1, G-1, G-2, and G-4 made the journey without incident. With them were three other vessels: the monitors Tonopah and Ozark, acting as tenders, and the destroyer Columbus, flagship of Capt. Grant.

As the undersea vessels glided up the river, their crews stood on deck, watching as the crowds in New London and Groton regarded them with curiosity.

Their destination was an abandoned Navy yard. But once they arrived, the place became something historic: the nation's first submarine base.

Editor's note: This story was drawn from documents at the Submarine Force Museum in Groton, several online references, and the archives of The Day and the New London Telegraph.