Wild Bird Surveillance for West Nile Virus

From 2000-2005, the Connecticut Mosquito Management Program (MMP) used reports and testing of dead wild birds, primarily crows, as one component of the system to monitor West Nile virus (WNV) activity in Connecticut. Since 2006, monitoring and risk assessment for WNV has emphasized mosquito trapping and testing results. In addition, suspected cases of WNV-infections in people are reportable to the Department of Public Health and in horses to the Department of Agriculture.

West Nile (WN) virus infection in mosquitoes is increased during the spring and summer when adult mosquitoes feed on birds. Infected mosquitoes carrying virus particles in their salivary glands infect susceptible bird species. Bird species capable of sustaining a sufficiently high viremia (level of virus circulating in the bloodstream) for several days then serve as a source of infection for additional mosquitoes. People, horses, and most other mammals are do not develop infectious-level viremias very often and thus are considered incidental-hosts not capable of infecting mosquitoes.

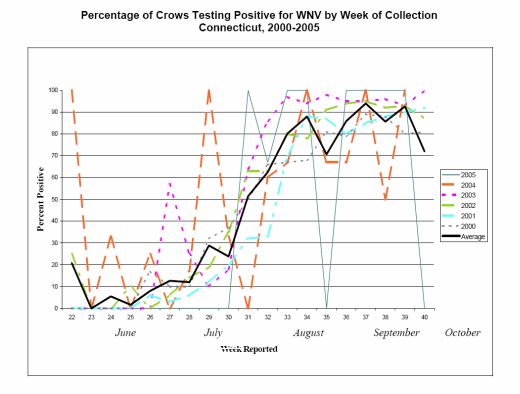

West Nile virus has been detected in dead birds of at least 317 species. Although most birds infected with WNV do not develop serious illness some species, particularly crows and jays, can develop fatal infections. During the first several years of WNV in Connecticut, many reports of dead crows were received by the Mosquito Management Program and served as a useful sentinel for the presence of WNV and to describe seasonal variation. Coinciding with an increased proportion of infected mosquitoes, the proportion of dead crows tested for WNV was greatest from mid-summer to early fall.

From 2000 to 2003, 92% of the human WNV infections acquired in Connecticut were preceded by a dead crow sighting in their town and 87% by a bird with laboratory-confirmed WNV infection. However, during 2004 and 2005, the numbers of dead crow reports and submissions for testing decreased sharply resulting in a reduced utility of this system for WNV monitoring purposes.

Mosquito surveillance has become more reliable than avian surveillance in describing the level of statewide WNV activity. Available resources are currently devoted to maintaining the statewide mosquito trapping and testing program conducted June through October. The risk of acquiring WNV infection varies by season and geographic region. In Connecticut, the risk is highest in August and September.

Dead birds are no longer being tested for WNV. Dead birds can be placed in a double plastic bag and placed out with the trash or brought to a municipal landfill. They can also be disposed of on-site by burying. As for all dead animals, avoid handling with birds with bare hands.

To assist state efforts to identify avian influenza, please report any findings of dead birds (>5) in one location or if you notice that numerous birds die in the same area over the course of several days. This is a situation where testing of the dead birds may be warranted. If you observe this type of die-off, please submit a report to the Wild Bird Mortality Reporting Website, and call the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Wildlife Division at 860-424-3011. Individual wild birds that are found dead can also be reported to the website. Waterfowl and shorebirds are the birds most likely to have avian influenza and are of particular interest. Sick or dead poultry should be reported to the Connecticut Department of Agriculture, State Veterinarian at 860-713-2505.

Dead Wild Bird Sightings Reported - Connecticut 1999 to 2005

| Year | Crows |

Other Species |

Unknown |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 1,040 | NA | NA | 1,040 |

|

| 2000 | 4,335 | 4,615 | 1,783 | 10,733 |

|

| 2001 | 3,189 | 2,011 | 900 | 6,100 |

|

| 2002 | 3,830 | 2,395 | 1,098 | 7,323 | |

| 2003 | 4,009 | 2,410 | 756 | 7,175 | |

| 2004 | 480 | 1,296 | 609 | 2,385 | |

| 2005 | 205 | 483 | 223 | 911 | |

Wild Birds Tested for WNV in Connecticut, 1999-2005

Content last updated in February 2025.