Connecticut Bureau of Natural Resources

"Then and Now"

Celebrating 150 Years of Natural Resource Conservation in Connecticut

Scroll through the topics below and learn how the Bureau of Natural Resources and wildlife in Connecticut have changed through time.

Anglers

During the 1950s through the 1970s, many anglers measured their success on the traditional opening day by being able to harvest their “daily limit.” Beginning in the 1980s and still growing in popularity today, many anglers now favor “catch and release.” While eating a healthy meal of freshly caught fish is still very popular, many anglers prefer to release their catch unharmed.

The future of our sport lies with our youth. In recent years, the number of people participating in fishing has been steadily increasing, reversing the continual decrease experienced over the past 20 years. The Bureau of Natural Resources is proud to offer free “learn to fish” classes, our youth fishing passport, a 50% reduction in license fees for 16-17 year olds, and electronic distribution of fish-related information via newsletters and social media. Today’s anglers still seek the thrill of the catch. Help us to grow the sport that we all enjoy so much – take someone fishing!

Pheasant Stocking

The first recorded release of ring-necked pheasants for the purpose of hunting was in 1908 when 88 birds were released in Windsor Locks. Pheasants, which could be produced on game farms, were brought into Connecticut to reduce hunting pressure on native gamebirds, which were declining due to population cycles and changing land uses. During the early days of pheasant stocking, helicopters were occasionally used to release pheasants at hunting areas.

Today’s pheasant program focuses on the release of adult birds by DEEP Wildlife Division staff during the fall hunting season and is funded through the sale of pheasant stamps and hunting licenses. No helicopters are used in the process!

Pheasant liberation by helicopter in Suffield, October,1949. Photo by D. N. Deane.

Moose in Connecticut

On September 15, 1956, Victor Piecyk took the first photograph ever of a moose in Connecticut. The moose was observed on his farm along Route 44 in Warrenville (Ashford). Although moose had been seen in the state before that time, none of the moose had been photographed. Therefore, the Connecticut Board of Fisheries and Game considered this the first official record of moose in Connecticut. The Board passed an emergency regulation on September 18, 1956, that gave full protection to moose. Unfortunately, this protection did not extend to the Warrenville moose which was reportedly shot on September 17, two days after being photographed. The next time a moose was observed in the state was in October 1964.

It is unclear whether moose were ever native to Connecticut. If moose did exist here during colonial times, they occurred in small numbers because Connecticut is at the southern fringe of their range. In 1935, George Gilbert Goodwin wrote in The Mammals of Connecticut: “The moose, if ever native to Connecticut, has long since disappeared from within the limits of this state.”

During the 1980s and 1990s, moose populations in Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire increased dramatically because of favorable habitat conditions and limited hunting. This resulted in a southerly expansion of New England moose populations and an increased frequency of dispersing moose wandering into Connecticut. Evidence of a resident, breeding moose population in our state was first documented in 1998.

During the 1980s and 1990s, moose populations in Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire increased dramatically because of favorable habitat conditions and limited hunting. This resulted in a southerly expansion of New England moose populations and an increased frequency of dispersing moose wandering into Connecticut. Evidence of a resident, breeding moose population in our state was first documented in 1998.

Today, the Wildlife Division estimates that population has grown to approximately 100 moose, mainly in extreme northern Connecticut. Biologists have been studying the distribution of moose in Connecticut, as well as whether or not the conditions and habitat in the state can support an increasing moose population. (The moose in the photo on the right was immobilized and fitted with a radio collar for the research.)

Electrofishing

Electrofishing is a common, efficient, and non-lethal tool biologists use to collect fish from a waterbody. A controlled amount of electricity momentarily stuns the fish that are within the electric field. Biologists often only have a few seconds to net a fish before it swims away. Once netted, biologists identify the species, collect measurements, take a sample of scales or fin clip, and safely return the fish unharmed.

The above photo represents the early days of the technology. Advances in electrical circuitry enabled biologists to safely control the use of electricity to collect fish. Connecticut was one of the early leaders in developing the science. Robert Jones, a leading fisheries biologist, led this Northeast Electrofishing Clinic in Lakeville in 1961.

Today’s Fisheries Division staff uses a combination of portable electrofishing equipment (above) and specially designed boats to sample fish populations. The data generated from electrofishing surveys are used in a variety of ways, such as determining species occurrence and abundance, population structure, the distribution of species, genetic relationships, and growth rates.

Shad Fishing on the Salmon River

These photos show the same view of the Salmon River in the Leesville section of East Haddam; the photo on the right is from the 1930s and the photo on the left is from present day. In the 1930s photo, the large white building is the powerhouse that sent electricity to the East Haddam swingbridge. (A fishway is now located in that spot.) The powerhouse was the first facility owned by a new company (at that time) called Connecticut Light and Power (CL&P). The small white building is the Board of Fisheries and Game’s shad hatchery, and behind that is an earthen dam. It was said that the Salmon River only had a small shad run until the Board operated the hatchery to augment commercial catches in the lower river. That generated a big return to the river and it was said that sport angling for shad was invented there.

The hurricane of 1938 took out the earthen dam and hatchery. CL&P sold the property to the State for $1 and all power generation was abandoned. The hatchery was never rebuilt and the dam remained breached until it was rebuilt in the early 1940s. The shad run petered out without the support of the hatchery.

The hurricane of 1938 took out the earthen dam and hatchery. CL&P sold the property to the State for $1 and all power generation was abandoned. The hatchery was never rebuilt and the dam remained breached until it was rebuilt in the early 1940s. The shad run petered out without the support of the hatchery.

In 1979, the Department of Environmental Protection (now known as DEEP) lowered the dam by 10 feet, demolished the foundation of the powerhouse, and built the present day fishway (which is barely visible at the right end of the dam’s spillway in the photo to the left).

Osprey Ground Nests

Ospreys used to build ground nests on Great Island, in Old Lyme. During the 1940s, approximately 200 osprey pairs nested on and around Great Island. Although trees were a preferred nest site, shoreline development in the early to mid-1900s caused a decline in trees available for nest sites. The habitat at Great Island afforded some protection to the ground nests as the area is separated from the mainland and ground predators, like raccoons and house cats, were limited at the time.

Today, an osprey ground nest is a rarity and seldom successful. Where trees have not been available for ospreys to use, the birds have adapted by using nesting platforms built specifically for them, as well as telephone poles, light stanchions, channel markers, and cell phone towers.

Ospreys prefer to build their nests in the large branches of dead trees. As development and storms eliminated many of these trees, some ospreys began to build their nests on the ground. Photo circa 1940 at Great island in Old Lyme.

An osprey family uses a nesting platform along the Connecticut shoreline. The development of nesting platforms has been a crucial management action for the recovery of osprey populations.

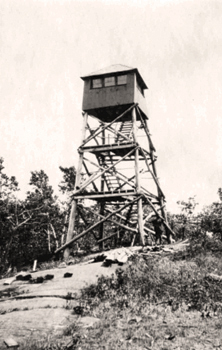

Forest Fire Wardens and Lookout Towers

In 1905, the Connecticut Forest Fire Law was established and the first fire wardens were appointed. State Forester Austin F. Hawes became the first State Forest Fire Warden on July 1, 1905. Prior to this time, there was little effort to stop forest fires unless they threatened valuable timber or buildings. A large number of forest fires at the time were attributed to railroad trains (about 30%), but the cause of at least half of the fires was unknown. The first fire tower built on state forest land was the Mohawk State Forest tower in 1924. Others were built later and the system of triangulation to pinpoint the location of fires was introduced.

Today, forest fire towers are no longer used to detect and locate forest and brush fires, and most towers no longer exist. One of the original fire towers, formerly located at Goodwin State Forest in Hampton, now sits on a high point at the DEEP Wildlife Division’s Sessions Woods Wildlife Management Area (WMA) in Burlington. Visitors to Sessions Woods can climb to the top of the tower to view the surrounding landscape as far as the trap rock ridges in Meriden and Southington. The tower was moved to Sessions Woods in fall 1988. The 30-foot tower, which had been partially disassembled, was trucked across the state to Sessions Woods, where it was reassembled and moved to its final destination on the WMA with the help of a Connecticut National Guard Sikorsky Sky Crane.

Mohawk State Forest, 1924

Shenipsit State Forest,1937

Turkey Hill State Forest, 1938

Sessions Woods Wildlife Management Area (formerly Goodwin State Forest Tower

Connecticut’s First Female Game Warden

In the “Twentieth Biennial Report of the State Board of Fisheries and Game, for the years 1932-34,” Arthur L. Clark, Acting Chief of the Division of Wildlife Restoration, covered the topic of “Women in Sports:”

“To encourage women to take a more active interest in the sport of fishing, a trout stream was leased in North Branford and maintained for their exclusive use in the spring of 1933. Miss Edith A. Stoehr was appointed warden and assigned to the Branford River. In the fall she was assigned to the public shooting ground in Farmington of which a small portion was reserved for the exclusive use of women.

Miss Stoehr was the first woman to be uniformed and appointed to regular active duties as a game warden. She is particularly fitted for these duties which are mostly concerned with offering encouragement and instruction in the sports of fishing and hunting with particular reference to the skillful use of fishing tackle and firearms.

The action by the Board has been met with encouraging response and many women have used these training areas. Since that time, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and other states have adopted a similar program and policy.”

Miss Stoehr, who was from South Wethersfield, won the appointment as the first female game warden in Connecticut by winning a fly-casting contest against four other women. Chief Game Warden Joseph Williamson decided that the contest would be the best way to select the new warden after a number of women applied for the job. A section of the Branford River, where Miss Stoehr was assigned, was stocked with trout and a nearby spacious log cabin lodge was built in 1940 to act as the headquarters for the “fisherwomen” who used the area. A clever photo caption from 1941 about the female only trout stream stated “Remember when men used to be able to get away from women for a spell by going fishing? Well, now women anglers don’t want any men around and they can get their wish on the Branford River, reputed to be the only stream of its kind in New England and one of three in the country, where fishing is exclusively for women.”

Efforts to encourage women to participate in hunting and fishing were just as ambitious in the 1930s as they are today. Although state hunting and fishing areas for exclusive use by women no longer exist in Connecticut, women have the opportunity to be introduced to hunting and fishing through DEEP’s Conservation Education/Firearms Safety (CE/FS) and Connecticut Aquatic Resources Education (CARE) Programs, as well as through the efforts of local sportsmen’s clubs and mentoring programs.

The first female game warden in Connecticut was hired in 1933. In 2016, DEEP’s Environmental Conservation Police Division currently has nine female officers in the field.

Chief Warden A. Joseph Williamson pinning badges on Edith Stoehr (left), Deputy Warden, and Miss Lois Stevens, Assistant Warden, after the two had won a fly-casting contest to determine the holder of the position to supervise and also act as angling instructors for women anglers on a section of the Branford River.

One of several current female DEEP Environmental Conservation Police Officers, Erin Flockhart and K-9 partner Ellie Mae.

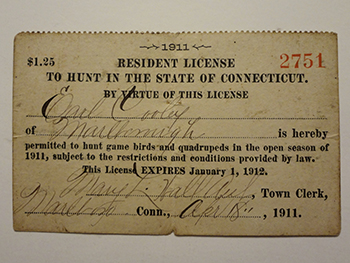

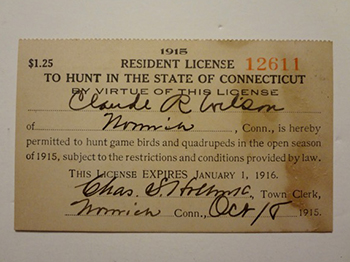

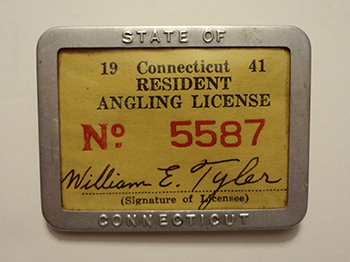

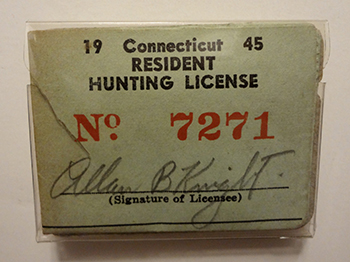

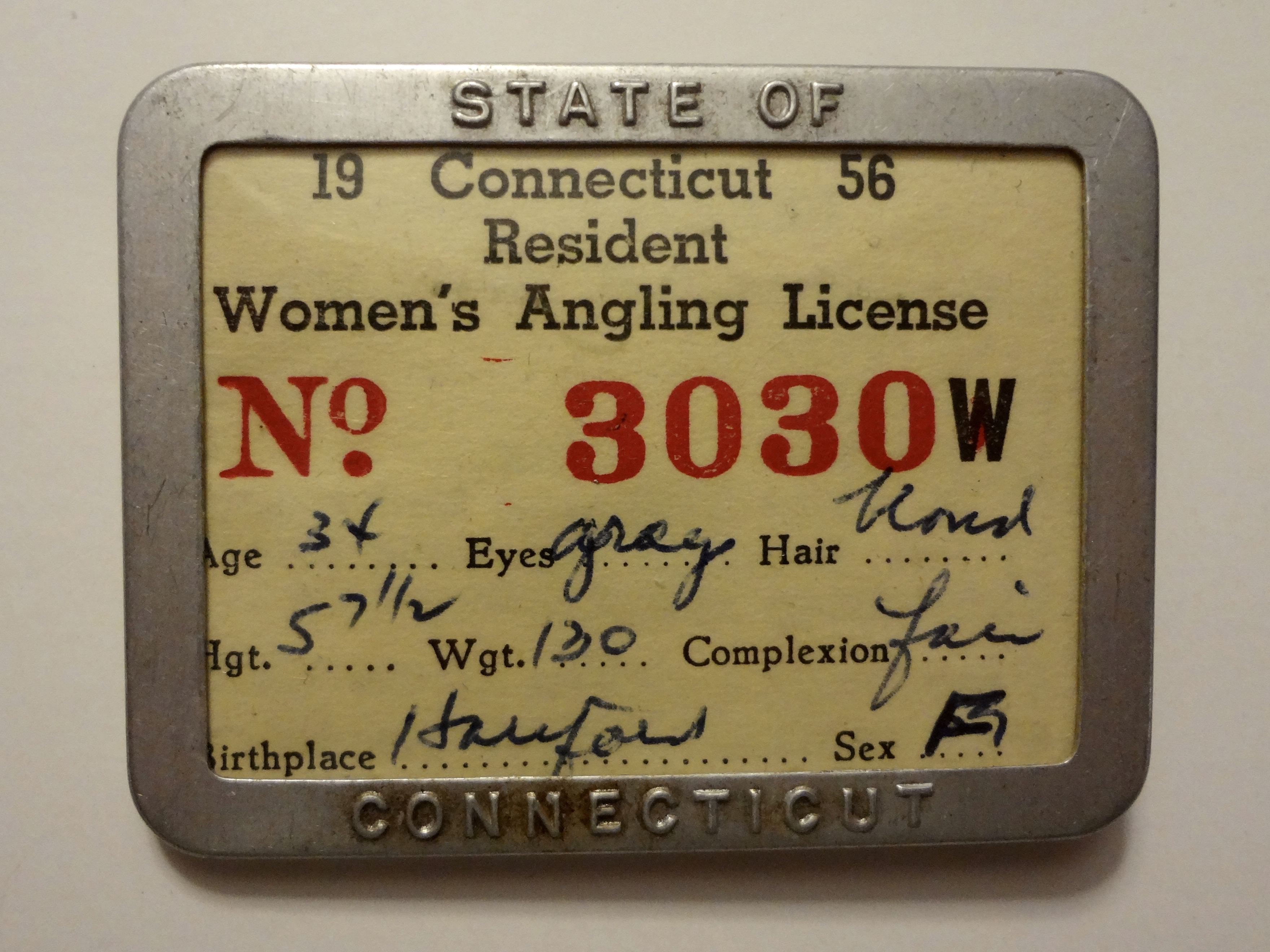

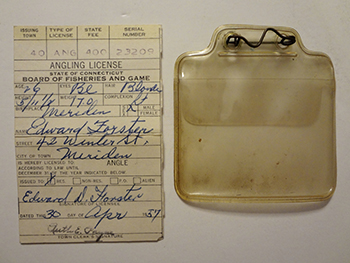

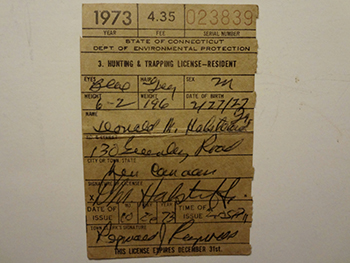

Connecticut Hunting Licenses

The information and photos for this article were supplied by Bill Myers, retired State Conservation Officer and Curator of CT Conservation Officer's Association Archives.

Licenses to hunt were not issued in Connecticut until 1906-1907. They were small, printed on heavy paper stock, and 4.5 inches long by 2.5 inches wide. This style continued through 1925. In 1926, the paper licenses began to be issued with a metal "pin on" button. Game wardens had complained that they needed to physically check each individual person for a license, and thought an outer clothing display of a license would make compliance checks easier and quicker. It became law that all hunters, fisherman, and trappers MUST display their license on outer clothing at all times while engaged in the sport. This style continued from 1926 through 1940. Many different styles of buttons were issued: hunting; angling; trapping; hunting and angling; hunting and trapping; hunting, angling, and trapping; landowner; and minor trapping. There were non-resident versions for each as well. The metal button styles and colors changed from year to year. The size of the metal buttons remained the same; about 1.5 inches round with a pin and clasp for outer clothing display.

In 1941, the department changed to an aluminum square metal frame “badge,” or holder. The badge was 2.5 inches long by 1.75 inches tall. It also had a pin on the rear side and a solid back that slid out, making it easy to change the license from year to year. Instructions on the rear side read, "Please bring this badge with you when applying for next year's license.” This style was used until the beginning of World War II. Metal was a commodity that was needed for the war. Hence, around 1942, the department discontinued the metal frames and developed a clear plastic holder with a cardboard backing. This license style was issued for about three to four years until the end of the war around 1946. Some overlap always occurred to use up the extra license carriers. Printed on the rear of the cardboard was "War-time license holder adopted to save metal—Win the War." These special licenses are priceless treasures in the history of the department and the issuance of licenses.

Aluminum frames were again issued in 1947, and this continued until 1956. In 1957, the department changed the style of licenses and began issuing small, clear plastic carriers to hold licenses. These plastic carriers still had a metal pin on the back as the law continued to require hunters, fisherman, and trappers to display the license on outer clothing at all times while engaged in the sport.

From 1957 through 1972, the licenses read "State of Connecticut Board of Fisheries and Game.” Beginning in 1973, they read "State of Connecticut The Department of Environmental Protection” after the new department was established in 1971.

Around 1990, the department stopped issuing plastic holders, and the law changed regarding outer clothing display. For the first time since 1925, sportsmen were now allowed to simply carry the license on their person without displaying the license on outer clothing.

This style continued until 2008. In 2009, the department began the new "On-line Licensing System" and licenses can now be printed from home computers, or at various DEEP offices, town halls, and outdoor equipment vendors.

Additional Notes:

The changing license styles were driven mostly by economics. Metal buttons, and then metal frames, were expensive. Plastic then came into existence and was substantially cheaper. Eventually, the plastic holders also became too expensive with limited budgets, and were discontinued. In our present day, the State no longer prints exclusive licenses, resulting in monetary savings.

For a period of 5 to 6 years, from about 1950 through 1956, "women’s" fishing licenses were issued.

Collecting old licenses is a hobby for many people. The hunting, fishing, and trapping licenses of the past can be highly collectible and expensive, and are considered quite historic.

These images of Connecticut hunting licenses dating back to 1911 highlight the various style changes:

1911 hunting license

1915 hunting license

1926 hunting license with first-of-issue metal button and matching number

1926 first-of-issue metal buttons

1941 first-of-issue metal framed license holder with paper insert

1941 to 1956 license holder with attached metal pin and slide out door

1945 WWII plastic hunting license holder

1945 WWII license holder with cardboard insert stating "War time license holder adopted to save metal - Win the War"

1956 women's angling license (last year of metal frames)

1957 new style of paper insert with plastic holder

1973 license now reads Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection instead of Board of Fisheries and Game

Connecticut's Commercial Fishing Industry

Many life-long residents are not aware that Connecticut has had a unique and lucrative commercial fishing industry since before the state was founded. Along with whaling products, finfish, lobster, and shellfish have been important state exports since the early 1800s. Concern for the welfare of the state’s shad and salmon fisheries was the motivation in 1866 for establishment of the Connecticut Fish Commission, precursor to today’s DEEP Bureau of Natural Resources and whose 150th anniversary we celebrate this year.

Commercial fishing for wild Atlantic salmon is now limited to waters of the North Atlantic due primarily to the long history of dam building in New England that cut the fish off from their spawning habitat. Connecticut’s shad fishery still markets fresh fish for local shad bakes, but recent landings are a small fraction of historic numbers. However, the good news is the Shad Monitoring Program – the longest ongoing program of the DEEP Marine Fisheries Division – has recorded a recent recovery in the Connecticut River shad population to abundance levels comparable to the 1980s.

Although these first two species of concern no longer dominate commercial activities in the state, several other species have taken their place. Since 1980, seafood landings in Connecticut ports have totaled five to 15 million pounds annually and generated five to more than 20 million dollars in annual dockside value (exclusive of shellfish aquaculture harvest). In recent years, fewer pounds have generated more dollars as the value has risen for some of the more than 75 harvested species; the peak value of over $10 per pound goes to sea scallops landed in Stonington.

Going back in history, an interesting comparison between 2010-2014 to 1939 landings reflects the effects of extended economic down turns. Commercial landings (reported, respectively, to DEEP and the Connecticut Board of Fisheries and Game) were about seven million pounds annually during both periods. However, annual dockside value for the top 10 species was $16.5 million in 2010-2014 but only $6.4 million in 1939 (inflation adjusted to 2014 from $0.4 million in 1939 dollars). Five of the top 10 species (whiting, scup, summer flounder, butterfish, and lobster) have not changed, although their rank order has. The remaining species reflect a change from small-scale fisheries targeting near-shore species in 1939 (mixed flounders, shad, and eel) to larger scale fisheries for offshore species in 2010-2014 (sea scallop and monkfish). Additionally, between the two time periods, squid and skates replaced all the flounder fisheries except one (summer flounder, whose landings remain similar but are now strictly regulated by state-specific quota, and with a price/pound doubled in value). Squid and skates have grown in commercial value as niche market products and bait for other fisheries. Red hake also has become more popular as processing techniques, especially for surimi, have expanded its marketability. Striped bass ranked in the top 10 in 1939; however, a 1967 state statute banned commercial fishing for this species in Connecticut waters. Striped bass still constitute a large portion of the commercial harvest in neighboring states and is a very popular target for Connecticut anglers.

In 2010-2014, an average of 181 commercial fishing vessels were licensed in Connecticut (range 149-217), with an average of 395 total crew members. In 1939, only 34 vessels were large enough to be registered with the state. However, an additional 230 smaller motorboats and row boats landed sea food in the state, providing jobs for a total of 562 crew. So 75 years ago, more boats and more people harvested similar pounds of sea food but for much less value in dock side dollars. Today, a growing number of health conscious consumers are enjoying high quality seafood while supporting this historic Connecticut industry.

Connecticut commercial fishing as it was in the 1950s. The captain lends a hand at washing the catch.

Connecticut commercial fishing in the 2010s is more mechanized and meets high sanitary standards.

View more information about Connecticut's commercial fishing industry.

150th Anniversary Main Webpage

Bureau of Natural Resources Through Time

Content last updated on February 20, 2020.