The Geology of Bolton Notch State Park

Bolton

Rock Types Found on Main Trail

- Igneous

- None

- Metamorphic

- Schist

- Gneiss

- Quartzite

- Sedimentary

- None

Rock Units

- Littleton Formation (Devonian): Gray to silver schist and micaceous quartzite

- Glastonbury Gneiss (Ordivician): Well foliated gneiss

- Clough Quartzite (Silurian): Medium grained well layered quartzite

Minerals of Interest

- Biotite

- Muscovite

- Quartz

- Garnet

- Staurolite

Interesting Geologic Features

- Folds

- Slumping

- Meandering Stream

- Caves

- Transgressing Sea

Figure 1: Old power lines that supplied electricity to the railroad.

Bolton Notch State Park has a wonderfully maintained State hiking trail that makes its way through the park. The trail is part of an old railroad bed that is adjacent to unused power lines, which once provided electricity to the railroad (Figure 1). The trail is very flat and wide, providing an excellent place to walk or ride a bike. The rocks at Bolton Notch State Park tell us that the area was once the site of an ancient transgressing sea, part of which can be observed along the old railroad.

Figure 2: Meandering stream cutting through schist.

Figure 3: a) Schist outcrop along trail b) Up close photo of schist with pencil for scale.

Running parallel to the blue trail, a small stream has undercut massive outcrops of schist. Schist is a type of metamorphic rock that has undergone intense heat, pressure, and hot fluids (Figure 3). By definition, schist contains more than 50% platy and elongate minerals such as mica and amphibole. This high percentage of platy minerals allows schist to be easily split into thin flakes or slabs. Most of the schist is covered with lichen and moss, making it difficult to see the features specific to schist. However, if you do find a piece of unweathered schist, it will appear incredibly shiny from the high concentration of mica minerals. Since schist can be easily split, all along the trail, large boulders have fallen from the outcrops and now lie at the base of the exposure (Figure 4). Likewise, in several areas, trees have actually begun to grow up through the rock.

Figure 4: Vegetation growing up through schist.

In addition to schist, there are a few outcrops on the blue trail of quartzite, a metamorphic rock formed from sandstone. As its name suggests, quartzite is primarily composed of quartz. The quartzite at Bolton Notch State Park is dark gray in color and is referred to as "dirty quartzite".

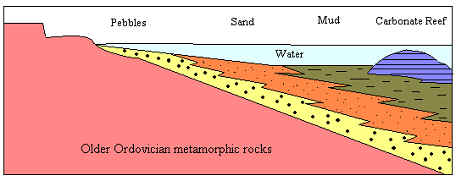

Although there is no trail leading up to the steep cliff (the highest point of elevation) at Bolton Notch, the hike up to the "notch" is the best area to explore this classic site. During the Ordovician period, a sea separated the North American continent from a volcanic island arc to the east. The rocks at Bolton Notch were predominantly formed from sedimentary and volcanic materials deposited as a result of this sea. As sea level rose, the sea transgressed the land, and the sequence of sediments found off shore moved landward. As a result, a sequence of sedimentary rocks formed due to the lithification of pebbles, sand, mud, and carbonate reef sediments, as seen in the cross section (Figure 5). The pebble deposits formed conglomerate, the sand formed sandstone, the mud formed shale, and the carbonate reef deposits formed limestone. However, at the end of the Ordovician period, these sedimentary rocks were intensely deformed by a westerly moving plate that collided with the volcanic arc. This collision produced the Taconic Mountains and metamorphosed the conglomerate, sandstone, shale and limestone once found at Bolton Notch. The more recent metamorphosed rocks include metaconglomerate, quartzite, gneiss/schist, and marble, formally conglomerate, sandstone, shale, and limestone, respectively.

Figure 5: Cross section of a transgressing sea once found at Bolton Notch. Illustration modified from University of Connecticut's Geology 102 Lab Manual (Fall 2002).

Another interesting feature at Bolton Notch State Park is located at the very top of the "notch". At the top of the cliff, in the marble exposure, there are several caves large enough to accommodate a human. Calcite is the predominate mineral in marble, and as a result, has a tendency to dissolve with the introduction of acidic materials. Over time, the acidic nature of rain has slowly dissolved the marble, and formed caves.