How To

Classroom Setup

Students will work in groups of three to four. Students will need access to the internet and large poster paper. In addition, students will take notes and write reflections in their journals.

Procedure

Part 1: Have students view the following images and develop questions about child labor in CT using the QFT technique:

Ask as many questions as possible in 2 minutes - No judgment!

- Categorize the questions as closed or open ended.

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of each kind of question? Prioritize three questions from your list.

- Which questions will help you to understand cause and effect on this topic?

- Which questions will establish context?

- Which questions will give some insights to the different perspectives on this topic?

- Which of their questions could best lead to more investigation?

Image 1

Messenger boys: they work from 5am to 11pm. New Haven, Connecticut. Lewis Hine. National Archives.

Image 2

Child tobacco workers. Hazardville, CT, 1919- Ct Historical Society

Image 3

10 year-old picker in Tobacco Field, Connecticut Lewis Wickes Hine-National Archives

Image 4

Children Tobacco-Pickers: they make 50 cents a day. Lewis Hine. National Archives

Image 5

Two of the youngest newsboys in Hartford, Connecticut. They are cousins, eight and ten years-old. August 25, 1924. Location: Hartford, Connecticut. Lewis Hine. National Archives

Image 6

Girl newsies: waiting for papers. Hartford, Connecticut, 1909. Photo by Lewis Hine. National Archives.

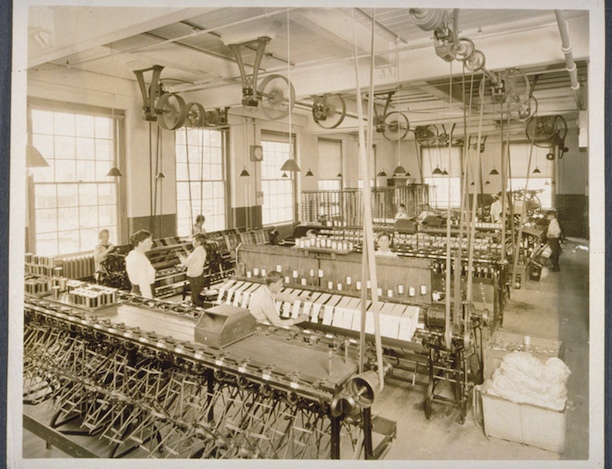

Image 7

Cheney Silk Mills, Manchester.

Image 8

Mill interior: Cheney Brothers Silk Manufacturing Company, 1918. Woman supervising boys at work-CT Historical Society. CT, Lewis Hine. National Archives

Part 2: Photography as a Tool for Reform

Have students read the following information about the role of Lewis Hine’s photography in bringing about reform.

- Why is photography a powerful tool to change public perceptions?

- Why do you think it took so long to change the federal labor laws?

- Is photography used today to advocate for social and political issues?

Child Labor Exposed: The Legacy of Photographer Lewis Hine

A camera was an improbable weapon against the growing evil of child labor in the early years of the 20th century. Then, children as young as five years old were working long hours in dirty, dangerous canneries and mills in New England.

Lewis Wickes Hine, a former schoolteacher, cleverly faked his way into places where he wasn’t welcome and took photos of scenes that weren’t meant to be seen. He traveled hundreds of thousands of miles, exposing himself to great danger. His exertions were ultimately rewarded with a law banning child labor in 1938.

He was born in Oshkosh, Wisc., on Sept. 26, 1874, and came late to photography. He was a 30 year-old prep school teacher at the Fieldston School in New York City when he got a bright idea: He would bring his students to Ellis Island to photograph the thousands of immigrants who arrived every day. Over five years he took more than 200 plates; but more importantly, he realized he could use photography to try to end child labor.

“There are two things I wanted to do. I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected. I wanted to show the things that had to be appreciated,” he said.

CHILD LABOR COMMITTEE

In 1908, Hine got a job for the National Child Labor Committee, reformers who fought the growing practice of child labor.

Between 1880 and 1900, the number of children between 5 and 10 working for wages had increased by 50 percent. One in six small children was then mining coal, running spinning machines, selling newspapers on the street or otherwise gainfully employed. They were robbed of an education and a childhood, trapped in a downward spiral of poverty.

Newsies, telegraph messengers and young mill-workers were exposed to vice and abused by their employers, their customers and even their parents.

Over the years, Hine photographed children working in gritty industrial settings that inspired a wave of moral outrage. With a new camera called the Graflex he took photos of child labor throughout New England.

Hine traveled far beyond the giant textile mills of Lowell and Lawrence, Mass. He went to silk and paper mills in Holyoke, Mass., textile and upholstering plants in Manchester, N.H., a cotton mill in North Pownall, V.T., and cotton mills in Scituate, R.I.

He went to the canneries in Eastport, Maine, where he saw children as young as seven cutting fish with butcher knives. Accidents happened -- a lot. “The salt water gets into the cuts and they ache," said one boy.

One day in August 1911 Hine saw an 8-year-old Syrian girl, Phoebe Thomas, running home from the sardine factory all alone. Her hand and arm were bathed with blood, and she was crying at the top of her voice. She had cut the end of her thumb nearly off and was sent home alone, since her mother was busy.

RELUCTANT EMPLOYERS

Employers didn’t want their practices exposed. Photo historian Daile Kaplan described how Hine operated:

Nattily dressed in a suit, tie, and hat, Hine, the gentleman actor and mimic, assumed a variety of personas — including Bible salesman, postcard salesman, and industrial photographer making a record of factory machinery — to gain entrance to the workplace.

Hine might tell a plant manager he was an industrial photographer taking pictures of machines. At the last minute he would ask if a child laborer could stand near the machine to show its size. He also interviewed mill owners, parents and local officials, pioneering tactics still used by 60 Minutes.

Hine confronted public officials with evidence and asked for a response. He asked the children about their lives. He told one heartbreaking story about a child laborer who worked in a cannery, so young and beaten down she couldn’t tell him her name.

Russell Freedman, in his book, Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labor, wrote, "At times, he was in real danger, risking physical attack when factory managers realized what he was up to…he put his life on the line in order to record a truthful picture of working children in early twentieth-century America."

FARM LABOR

That picture included child labor in rural New England, such as in Connecticut's tobacco fields and on Western Massachusetts farms. Hine photographed eight-year-old Jack driving a load of hay and taking care of livestock. He was 'a type of child who is being overworked in many rural districts,' wrote Hine.

By 1912, the NCLC persuaded Congress to create a United States Children's Bureau in the Department of Labor and Department of Commerce. The Children’s Bureau worked closely with the NCLC to investigate abuses of child labor.

Years of political battles followed, until finally in 1938 Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act. The law prohibits any interstate commerce of goods produced by children under the age of 16. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed it into law on June 25, 1938.

By then, the public had lost interest in Lewis Hine’s work. He died two years later, broke, in Dobbs Ferry, N.Y. His son offered to donate his photographs to the Museum of Modern Art, but he was rebuffed. Today, Hine's photographs of child labor are held in collections at the Library of Congress and the George Eastman House in Rochester, N.Y.

The National Child Labor Committee Collection at the Library of Congress consists of more than 5,100 photographic prints and 355 glass negatives.

And today there is a Lewis Hine award for people who have done outstanding work in helping young people.

—From: Child Labor Exposed: The Legacy of Photographer Lewis Hine

Part 3: Child Advocacy

Have students work in groups to answer the following questions. Students will review the following four primary documents and complete the following chart. These documents detail the investigation and suggestions of the State of Connecticut to address the use of child labor. Download worksheet

|

Image/Document |

Specific Issues |

Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

|

Doc 1 |

|

|

|

Doc 2 |

|

|

| Doc 3 | ||

| Doc 4 |

How would the following groups respond to the recommendations in each document? Explain.

- Labor Unions

- Democrats

- Republicans

- Progressive Reformers

- Teachers

- Employers

- Child Workers

- Parents

Who had the most power?

Should the role of government include protection of children? Explain.

Document 1

Page 9, Recommendations, Report of the Bureau of labor on the conditions of wage-earning women and girls by Connecticut Bureau of Labor Statistics. Charlotte Molyneux Holloway. Hartford, 1914

Document 2

Page 143, Recommendations, State of Connecticut Report of the Department of Labor on the conditions of wage-earners in the state. Printed in compliance with statute, 1918.

Document 3

Page 266, Ignorance an Economic Waste, Annual report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, of the State of Connecticut. 1894,

Page 277, What Some of the Teachers Say

Document 4

Page 6, Forward, Industrial instability of child workers. A study of employment-certificate records in Connecticut, Robert Morse Woodbury, 1920