Salmonellosis in Connecticut, 2020

Authors: L. Kasper, MPH, J. Hadler, MD, MPH, Connecticut Emerging Infections Program at the Yale School of Public Health.

Salmonella are bacteria that can cause illness in humans called salmonellosis. Most cases of salmonellosis occur through consumption of contaminated food or water (1). Live poultry can act as a reservoir of Salmonella and have been associated with annual national outbreaks (2). Illness is mainly characterized by symptoms of gastroenteritis and their consequences in afflicted individuals. While salmonellosis is reported year-round, there is particularly high incidence during the summer months (3). This analysis was prompted by news reports of an increase in live backyard poultry sales during the early stages of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, which may have led to an increase of poultry-associated salmonellosis.

In Connecticut, public health surveillance of Salmonella is conducted by the Yale Emerging Infections Program (EIP) on behalf of the Connecticut Department of Public Health (CT DPH). Active laboratory surveillance for Salmonella is conducted based on detection in stool, urine, blood, and other bodily fluids followed by case interview using a standardized questionnaire. The case interview includes questions about exposure to live poultry.

Connecticut Salmonella surveillance data during 2014–2019 were used to determine expected Salmonella incidence and compared to 2020 incidence. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provided a dataset of all Connecticut cases linked to annual national backyard poultry outbreaks during 2014–2020. Live-poultry exposure associated cases were defined as individuals who self-reported exposure to live poultry within 7 days of illness onset. National backyard poultry outbreak associated cases were individuals who, prior to 2018, were linked by pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) or, more recently, by whole genome sequencing (WGS) to the national poultry outbreak serotypes. The expected number of outbreak cases, using the exposure cases as a reference, and the actual number of cases associated with backyard poultry outbreaks during 2014–2019 were compared to those reported in 2020.

Analyses were performed using all Salmonella cases, and exposure cases and outbreak cases, to identify changes in laboratory-confirmed Salmonella incidence. Further analyses were done on both groups to determine whether there were changes in demographic characteristics, temporal distribution, and relative and absolute changes in incidence.

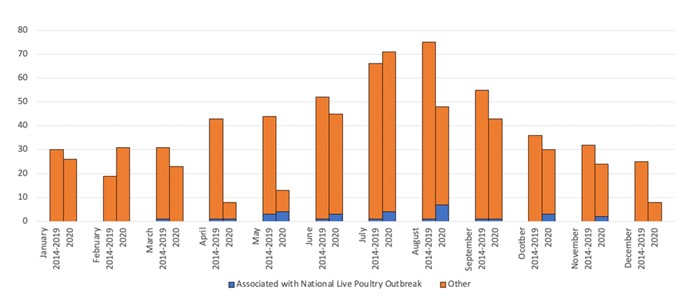

There was a decrease in overall incidence of reported Connecticut Salmonella cases from an annual average of 467.9 cases reported during 2014–2019 to 330 cases during 2020. Most of the decrease occurred during the months of March–May (Figure). Statistically significant changes were observed in demographic characteristics of cases. During 2020, 49% of cases were ≥45 years of age, an increase from 41% during 2014–2019 (p=0.01). The percentage of individuals identifying as non-Hispanic White decreased from 61.3% to 53.3% (p=0.005).

There was an increase in live-poultry exposure associated cases from an annual average of 4.0% in 2014–2019 to 8.8% in 2020 (p<0.001), with more cases reporting exposure to live poultry in 2020 (29) than expected (18.8) based on the previous 6 years. The temporal distribution of national backyard poultry outbreak associated cases shifted from early summer to late summer and early fall (Figure). Of those reporting live poultry exposure in Connecticut during 2020, 90.0% reported exposure to chickens and 16.7% to ducks, which was a slight change from previous years.

Discussion

The incidence of reported Salmonella cases in 2020 was different than previous years in at least two ways, First, there was an overall decrease in incidence relative to previous years. This decrease was most pronounced during March-May, coinciding with the most restrictive period of the pandemic response. A portion of the decrease in Salmonella incidence, especially during April and May, may be due to a hesitancy to seek care for diagnosis and treatment for Salmonella symptoms due to fear of contracting COVID-19 and a shift away from in person acute diagnosis and care to telemedicine (4). Given salmonellosis often resolves on its own, individuals who get tested represent a fraction of the population infected, making it challenging to determine the actual number of cases in the population. The COVID-19 pandemic might have exasperated this issue, especially early in the pandemic, when data indicates only more severely ill people sought care in person (4). Another possible contributing factor is that an increased risk of contracting Salmonella has been linked to eating at restaurants and social behavior (5); it is possible incidence decreased as a result of closures of restaurants.

Second, despite a decrease in overall numbers of reported cases of salmonellosis, the number of cases who self-reported exposure to live poultry in the 7 days before illness onset was above expected levels from June to October 2020. In previous years, the number and proportion of cases who self-reported live poultry exposure peaked in early summer. In 2020, the greatest absolute increase in the number and proportion of cases reporting live poultry exposure occurred during late summer and early fall, even while numbers of reported salmonella cases were lower than expected. While this increase in live poultry-associated salmonellosis might be related to the reported increase in live backyard poultry sales during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is possible a phenomenon unrelated to the pandemic is occurring and merits continued monitoring. The CDC has recently published recommendations for prevention of salmonellosis among backyard flock owners and stores that display live poultry (2).

Key messages for providers

- Ask about exposure to live poultry when taking a medical history of a person with symptoms of bacterial gastrointestinal illness.

- Be aware of CDC guidance for prevention of salmonellosis targeted at backyard poultry flock owners and persons otherwise buying live poultry including chicks and ducklings (2).

References

- CDC. Salmonella. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- CDC. Salmonella. Outbreaks of Salmonella Infections Linked to Backyard Poultry. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/backyardpoultry-05-20/index.html. Accessed July 15, 2021.

- CDC. Salmonella. Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/general/prevention.html. Accessed July 19, 2021.

- Weiner, J. P., Bandeian, S., Hatef, E. In-Person and Telehealth Ambulatory Contacts and Costs in a Large US Insured Cohort Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network. Mar 2021 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2777779. Accessed July 22, 2021.

- Angulo, F. J., Jones, T. F. Eating in Restaurants: A Risk Factor for Foodborne Disease? Clinical Infectious Diseases. Nov. 2006 43(10), 1324-1328. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/43/10/1324/516737. Accessed July 22, 2021.

Figure. Salmonella cases by month of surveillance year, 2014-2019 vs 2020, Connecticut.

This page last updated 8/20/2021.