Rhododendron (Rhododendron)

Plant Health Problems

Diseases caused by Fungi:

Leaf spots.

Several fungi cause leafspotting on rhododendron leaves, often as a secondary effect of the shrub being in poor condition from some other cause. Leaf spots are most prevalent after periods of cool, wet spring weather.

These fungi generally do not cause serious damage to the plant; if the primary cause of the poor condition is found and corrected, spraying is usually unnecessary. Removal and composting of affected leaves after they fall reduces the possibility of spread. For more information, see the fact sheet on Common Problems of Rhododendron, Mountain Laurel, and Azalea.

Azalea leaf scorch, Septoria azaleae.

Small yellow spots on azalea leaves become dark reddish-brown with purple borders.

Generally, fungicide sprays are unnecessary. Many newer cultivars are resistant to leafspotting fungi and to leaf scorch.

Leaf gall, Exobasidium vaccinii.

This fungus is common on members of the rhododendron family, especially on cultivated and wild azaleas. The shoot leaves become swollen and curled, forming an irregular gall which is pinkish, later becoming white when spore formation occurs. On rhododendrons the flower parts may be involved but on azaleas it is chiefly leaf tissue. These swellings are known as pinkster apples, or swamp apples, or honeysuckle apples.

The disease may be reduced by hand-picking and destroying all galls. Many of the newer varieties are resistant.

Rust, Pucciniastrum myrtilli.

Many of the Heath family are susceptible to rust, including azaleas, rhododendrons, and blueberries. Small pustules appear on the underside of leaves. These pustules burst open to discharge bright yellow or brownish spores that reinfect the rhododendrons or azaleas. The alternate host is the eastern hemlock, and the clustercup stage appears on its needles. This stage is not necessary to the spread of the fungus among the Heath family as the summer stage can overwinter on rhododendron.

Control of this disease is usually not necessary. This disease is relatively uncommon in landscape plants as many of the newer varieties are less susceptible.

Powdery mildew, Microsphaera penicillata.

Infection appears as a whitish dust on azalea leaves during hot humid weather.

Deciduous azaleas are very susceptible; many cultivars of azalea and rhododendron are for all practical purposes resistant. Powdery mildew can be minimized by improving air circulation around the plant. Chemical controls are usually not necessary.

Azalea bud and twig blight, Ovulinia azaleae.

The first sign of this disease is the dwarfing of flower buds followed by their browning and death in late summer or early fall. The fungus can be found fruiting on the buds, the fruiting bodies resembling tiny pins stuck into the buds.

Picking and composting infected plant parts either in late fall or early spring will help materially to reduce infection. Seed pods can also be removed as soon as flowers have withered.

Damping-off and root rot, Rhizoctonia solani.

This fungus is widespread and causes more trouble with rhododendrons than is generally realized. Rhizoctonia can kill small or large bushes or just keep them in poor condition. Symptoms may include small necrotic spots on leaves, which later become dark brown or black. Defoliation follows severe leaf spotting. The fungus is omnipresent in the soil and appears to be most virulent at high humidity levels. Microscopic examination of roots and crown are the surest diagnosis.

Cultural practices to control this disease include improvement of drainage and avoidance of excess irrigation.

Shoestring root rot, Armillaria mellea.

Symptoms appear as a yellowing of leaves and a progressive, general decline and dieback of branches and limbs. This decline often develops over a period of years. The soilborne fungus penetrates the roots and/or bark at ground level and gradually girdles the base of the plant. Its presence is indicated by whitish mycelial fans under the bark and the presence of shoestring-like rhizomorphs in the soil around the roots, along the roots, and on and under the bark of the crown. Plants which have root damage due to drought and other stresses are more susceptible to this disease.

Control of this fungus is difficult. Removal of dead plants and especially dead wood is important. In addition, the fungus is completely intolerant of drying, so the chances of spreading the fungus to uninfected plants will be reduced by thorough drying of wood chips and leaf mold before using them as a mulch or amendment.

Diseases caused by Physiological/Environmental Factors:

Chlorosis and winter injury.

Rhododendron leaves normally remain green in winter but curl and hang down in very cold weather. Browning on the margins and tips of the leaves occurs when loss of water from the leaf surface is greater than the ability of the roots to absorb water. This happens when roots are injured by recent transplanting, cultivation, insects, fungi, or other mechanical agents. Mole tunnels around roots indicate the presence of grubs. However, these runs may be used in winter by mice which eat the plant roots. Root injury is aggravated by planting in an exposed location. Rhododendrons prefer partial shade. Marginal burning is often followed by semi-pathogenic fungi (see Leaf spot). Concurrent with or independent of this burning is a yellowing of the interveinal areas leaving the tissue green immediately adjacent to the veins. Root injuries may be responsible for this chlorosis. Other causes include soil that is not acid enough, or is poorly drained, or is receiving water from a down-spout from a roof. The addition of too much fertilizer or too much phosphate or lime can have similar results. Careful examination on the spot is very important. All pertinent facts submitted with root and soil specimens for laboratory examination aid greatly in proper diagnosis.

Ice injury.

Bright yellow or brown spots regularly spaced along the mid-vein may indicate this trouble. Glaze ice formed on rolled leaves may act as a focusing agent for the sun's rays if ice has not fallen by the time the sun comes out. The injury remains static, with sharply defined edges, as differentiated from the start of nutritional troubles which progress and have indefinite edges. For more information, see the fact sheets on:

Weather-Associated Problems of Ornamental Trees and ShrubsWinter Injury and Drying of RhododendronWinter Injury on Woody Ornamentals

Insect Problems: Azalea bark scale, Acanthococcus azaleae.

Azalea bark scale, Acanthococcus azaleae.

Azalea plants growing outside are frequently infested with the white cottony or woolly masses of this insect fastened to the twigs, usually in the axils of the branches or close to the buds. Both sexes are enclosed in a felt-like sac. Among the compounds registered for control of this pest in Connecticut are ultrafine horticultural oil, insecticidal soap and malathion. A dormant application of ultrafine oil will control overwintering insects and conserve natural enemies. Insecticidal soap, the summer rate of ultrafine horticultural oil or malathion, applied in late June through late July, will control crawlers. Imidacloprid applied to the soil as a systemic can provide season-long control. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Azalea leafminer (also known as azalea leafroller), Caloptilia azaleella.

Azalea leafminer (also known as azalea leafroller), Caloptilia azaleella.

The insect is a small yellow caterpillar 1/2" long. It first lives in the leaf. However, before completing its feeding stage, it leaves the interior of the leaf, folds over the margin and continues feeding on the surface. Injured leaves turn yellow and drop. When mature the larva moves to a new leaf, rolls it into a case and pupates. This insect probably overwinters as a pupae or partially grown larvae. The golden adult moth is about 1/2" long and very secretive. Eggs are laid singly on the underside of a leaf near the midvein. Among the compounds registered for control of this pest in Connecticut are malathion or acephate sprays, applied in June, for control of the larvae. Imidacloprid applied to the soil as a systemic can provide season-long control. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Black vine weevil, Otiorhynchus sulcatus.

Black vine weevil, Otiorhynchus sulcatus.

The larvae of this weevil often injure plants in nurseries and ornamental plantings by feeding on the roots. The grubs devour the small roots and gnaw the bark from the larger roots, often girdling them. The larvae stage do not grow as well on rhododendron root systems as on strawberry or yew, but this may actually increase the likelihood of rhododendrons becoming girdled. The tops of girdled plants first turn yellow, then brown, and the severely injured plants die. Large landscape plants tolerate root grazing quite well, but leaf notching by adults can be unsightly. The 1/2" long adult weevil is black, with a beaded appearance to the thorax and scattered spots of yellow hairs on the wing covers. Only females are known, and the adults are flightless. They feed nocturnally, notching the margins of the foliage. The legless grub is white with a brown head and is curved like grubs of other weevils. Adults and large larvae overwinter, emerging from May - July. The adults have to feed for 3 - 4 weeks before being able to lay eggs. Treating the soil with insect pathogenic nematodes can control the larvae, and should be the first line of defense in the landscape. Acephate and fluvalinate are among the compounds registered for control of this pest in Connecticut, and may be applied when there is adult feeding and before they start laying eggs. The usual timing for these foliar sprays is during May, June and July at three week intervals. Insecticide resistance is very common; be aware that adults may appear to be dead following contact with fluvalinate, but may recover from poisoning within a few days. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Lacebugs, Stephanitis pyrioides and S. rhododendri.

Lacebugs, Stephanitis pyrioides and S. rhododendri.

The adults and nymphs of the azalea and rhododendron lacebug, respectively, suck sap from the undersides of leaves. The results of infestation show on the upper leaf surface as a mottled or white peppered appearance, and the under surface of the leaf is brown-spotted with excrement. The winter is passed as eggs inserted on the underside of the leaf, usually near the midrib. They hatch in May, and the nymphs become mature in June and lay eggs in June and July for the second generation, the nymphs of which appear in August. These nymphs mature and the adults lay eggs in the leaves that hatch the following spring. The control measures consist of spraying the undersides of the leaves to control the nymphs and adults by using acephate or insecticidal soap, which are among the compounds registered for control of this pest in Connecticut. The first spray is required late in May and the second in July. Imidacloprid applied as a systemic to be taken up by the roots will give season-long control. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Pitted ambrosia beetle, Corthylus punctatissimus.

Plants growing in the shade or those that are mulched are sometimes injured by small whitish larvae that make horizontal galleries in the wood at the base of the stem. The damage can lead to wilting and dying. Adults overwinter in the tunnels where pupation occurred. The adult is a stout beetle about 1/8" (4 mm) long, shiny dark brown to black. The wilted branches may be cut out and burned. Spraying the base of the plants with permethrin, which is one of the products registered for use on this pest in Connecticut, late in the spring will help control the adults. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

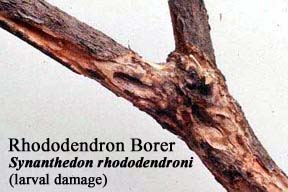

Rhododendron borer, Synanthedon rhododendri.

Rhododendron borer, Synanthedon rhododendri.

Rhododendron trunks and branches are sometimes severely injured by white larvae that tunnel under the bark. Severe wounds are formed, often from multiple larvae infesting adjacent tunnels. The top or side branches wilt and sometimes break off. The larva matures in October and is then about 1/2" long. It overwinters in the burrow and pupates in the spring. The moths appear from May through July and the females lay eggs on the twigs, especially near wounds. The clearwing moth resembles a yellowjacket wasp, has a wingspread of about 1/2", and flies during the day. There is one generation each year. One method of control is to cut out the borers and injured stems and dispose of the refuse. The area around wounds can be enclosed with a paraffin film to protect them from further egg laying. Spraying with permethrin, which is one of the products registered in Connecticut for use against this pest, at the time the moths are active may help control this pest. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions. Adult activity may be monitored with pheromone traps for peach tree borer; if there is a small enough borer population, the traps may also disrupt mating by trapping out the male population.

Rhododendron leafminer, Lyonetia latistrigella and L. ledi.

These tiny moths lay eggs singly into the undersides of young, opening leaves of woody plants in the heath (rhododendron, azalea, mountain laurel) and rose families. Initially, mines are serpentine but as the larvae grow, the mines enlarge to form a blotch. Mature larvae pupate in silken cocoons suspended by strands of silk from the undersides of leaves. In subsequent generations, moths again lay eggs in newly unfolded leaves so that as the season progresses, new foliage continues to be damaged. Each generation is completed in two to five weeks so that in warmer seasons there may be up to eight or nine generations. Among the materials registered in Connecticut, imidacloprid has provided season-long control of rhododendron leaf miner. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Rhododendron stem borer, Oberea myops.

Small, thin longhorned beetles feed on the undersides of leaves at the midvein causing the leaf to curl abnormally. Females lay eggs in new shoots just below the bud in late June to early July. Larvae bore into the twig and most likely overwinter there. The second year, the larva continues boring downward and spends the second winter in the roots. This year many holes are made to remove frass from the tunnel and "sawdust" gathers on the ground around the stem. At maturity, the creamy white larva is 1" long. When needed, permethrin, one of the products registered for use against this pest in Connecticut, applied to the stems from late May through mid-June, should control this pest. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions. Alternatively, prune out and dispose of infested shoots.

Rhododendron tip midge, Clinodiplosis rhododendri.

This insect usually overwinters in the soil as a prepupa. Pupation occurs in spring, with the adult midge emerging just as the hosts begin vegetative growth. There may be two additional generations yearly corresponding with flushes of rhododendron growth. Eggs are laid in clusters on the undersurfaces of leaves that are emerging from buds. Larval feeding causes a downward and inward rolling of leaf margins. Larvae mature in about seven days, drop to the ground, burrow in and make a cocoon. Among the compounds registered for control of this pest in Connecticut are dimethoate and spinosad which can be applied to foliage in mid- to late May. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Southern red mite, Oligonychus ilicis.

This mite overwinters as reddish eggs on the under-surface of leaves. Adults and nymphs feed on both the lower and upper leaf surfaces. The oval-shaped adults are normally red, but can be green with lighter colored legs. Multiple generations occur each season. If not controlled in the spring, populations will rise again in the fall. Among the compounds registered for control of this insect in Connecticut are horticultural oil used as a dormant or summer spray. Additional materials appropriate for commercial growers include hexythiazox or abamectin (a restricted use product). Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.

Twobanded Japanese weevil, Callirhopalus bifasciatus.

The weevils, which consist of only females, feed on the margins of the leaves of azalea, barberry, rhododendron and other shrubs, leaving characteristic crescent-shaped notches. The weevil is about 1/5" long, robust, and varied brown in color. The wing covers have faint whitish lines and whitish spots on the apex. Spray acephate which is registered for control of this pest in Connecticut, in early August if many adults are noticed and damage is intolerable. Consult the label for dosage rates and safety precautions.